Simulation Over All Else: From Wargame to Accidental LARP

Sam Sorensen discusses the 'Over/Under' experiment, the reification of shared reality, and the limits of game mastering.

Some important links:

Sam’s Over/Under Writeup

Cataphracts Design Diary #1 - Sam Sorensen

1. Hi Sam! Can you introduce yourself and tell us about your connection to tabletop RPGs?

Hi Dave! I’m Sam Sorensen, a game designer, writer, editor, graphic designer, and sometimes-adjunct instructor based in New York. I’ve been releasing RPG stuff in some shape or form for about six years now, and have been more-or-less full-time for the past three. I do a lot of freelance work for various clients—mostly editing manuscripts or doing graphic design and layout for publication—as well as writing and releasing my own projects. These days, I mostly work in what might be called the “post-OSR” space, the particular branch new-old-school design and play that emphasizes simulation over all else. I’ve released my own or worked on third-party content for Mothership, MÖRK BORG, Troika!, Old School Essentials, quasi-system-agnostic B/X old-school rulesets, actual system-neutral adventures, and regular old Dungeons & Dragons, plus probably one or two other rulesets or systems I’m forgetting. I also have a semi-regular blog, mostly discussing my current projects, the craft and industry of RPGs, or game studies topics.

2. That’s excellent, Sam. Can you tell me what Over/Under was, and what your role was in it?

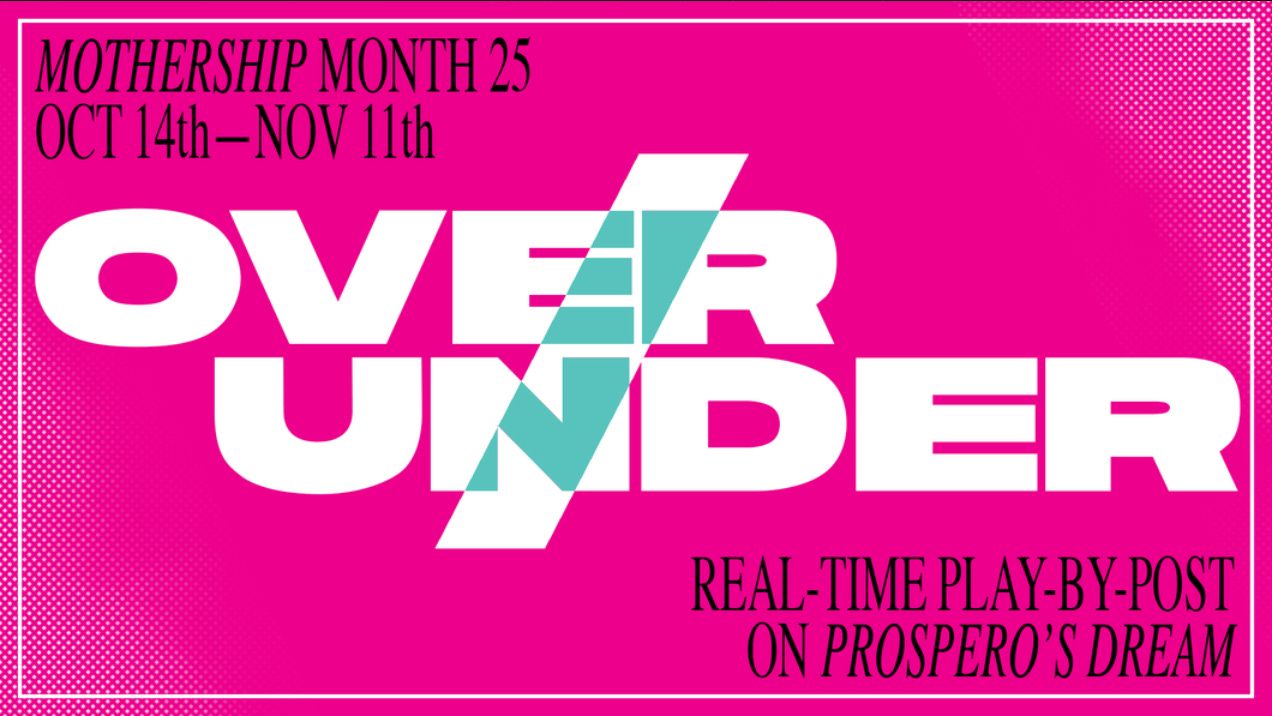

This is a more complicated question than it sounds, haha. In essence, OVER/UNDER was a real-time play-by-post game played out over the course of a month on a large Discord server, set in the world of Mothership, the sci-fi horror RPG. In its initial conception it was sort of a hybrid wargame, economic game, and social deduction game, with the faction Bosses engaging more in the war side of things and the Denizens focused more on the economic and social sides. Factions scaled with the number of Denizens they recruited (so Bosses wanted to recruit them) but Denizens, if they disagreed with their Bosses, could vote them out (so Bosses needed to be cautious with their numbers). We had a bot to handle some of the transactions, a ton of spreadsheets to handle the wargame, and the server for communications and espionage. In my head, it was sort of like a game of Warhammer stapled onto a game of For-Ex stapled onto a game of Mafia, with each of the three influencing the other. But! in practice, OVER/UNDER changed quite a bit over the course of play. As more and more players joined—we ended up with something like 1,200 in total—it shifted more towards a kind of larp-esque model. Denizens became focused not so much on pursuing faction goals or chasing wealth (the two stated objectives of the game) but rather their own individual storylines and play groups. The distinctions between “in-character” discussion and “out-of-character” discussion—something that the original ruleset more or less doesn’t acknowledge the difference between—became very sharp and important. One of my friends described the game as a “digital ren faire,” and that felt very accurate. The point became less about winning or chasing objectives and more about telling compelling stories or chilling with your friends. This isn’t a bad thing, obviously, but it did change the vibe significantly.

For me, as the original game designer and then the Warden—the term Mothership uses for its GMs or referees—I had many responsibilities. Mainly, I had to process orders from each of the roughly twenty faction Bosses: moving soldiers, pushing cargo, running intelligence operations, holding elections, and so on. I also had to answer rules questions, juggle daily processing of faction income, maintain some of our backend server stuff for the Discord bot, and try to keep a handle on things. When factions took larger actions (holding votes of no confidence against Bosses, changing their bylaws, etc.), I also had to be involved to make sure all of the official game documentation was up to date. As the game shifted from its earlier wargame form to a more larp-adjacent style, this sometimes got tricky: because the server was so big, I’d very often get pinged into a channel asking a question that I had zero context for. In many cases, I would miss significant events or developments for hours, days, or sometimes weeks at a time, just because of the scale of the game. I spent a lot of time talking with players, trying to understand how the game was moving, and make some attempt to keep up. At a certain point, it felt less like I was a game designer and more like an event planner—and while I like to think of myself as a reasonably competent designer, I am, tragically, a pretty crummy events manager, haha.

3. Okay, it’s time to fess up to our readers here. I was one of the eighteen starting bosses in the game. And I lasted exactly one week before my denizens (and I do believe my co-bosses) voted me out. The cause of action was that I wasn’t reading and responding to enough messages each day. As you know, the messages were a constant stream all hours of the day and night. I can confirm that it was some of the most intense roleplaying I think I’d ever seen in an online game. What do you think the motivation was for everyone to lean in so hard on the roleplay, even to the point of abandoning the core objectives of the underlying game?

There’s an effect that happens in roleplaying games where a player says “I am Garzag the Mighty!” or whatever, and the GM says “Yes! You are Garzag! That is true,” and suddenly the player feels highly validated, highly legitimized, as though what was just a silly OC character has now become “real.” I’m sure there’s a game studies term for this that I don’t know, but this is a continual pattern and cycle of reification, of looking at each other and saying “Yes, we all agree that this is happening.” This happens at every table, all the time, and for many players, it can be quite alluring, quite appealing—quite fun. I’ve found that many players who otherwise would not dream of writing fiction or acting in a play or otherwise engaging in creative activities can, at the RPG table, suddenly become quite animated and engaged, largely because of this process of having somebody in a position of relative authority say “Yes, you are true and valid.” That’s obviously reductive, oversimplified, but I think that that effect of continual affirmation and reification of a shared imaginary space—especially when paired with the personified, embodied agency so common in RPGs—is extremely potent.

At a regular RPG table, though, there’s only so much of this that can happen at once. Most tables only have a handful of players, typically with only one GM. Even in GMless or shared-GM games, you’re still limited by a relatively small number of overall participants. And in all cases, you’re limited by time. But in OVER/UNDER, suddenly many of those limits went away. Suddenly, there were dozens or even hundreds of people who all more-or-less agreed with you and your reality, and that cycle of reification and validation suddenly exploded in scope and scale. Here were hundreds of people willing to take your ideas and say “Yes, this is real, this is valid, this is true.” Many players—and I say this less a boast than an observation of aesthetics—described the game as “the most immersive experience they’d ever played.” “Immersion” is one of those squirrelly words that can mean a lot of things to a lot of people, but I think in this case it refers to this shared energy, this continual affirmation that this world you existed in was real, at a level you couldn’t comprehend, Even when you discovered somewhere new you hadn’t before (and again, much of the server felt like a place more than a simple chatroom), that world was still validated and upheld by your fellow players. And with the game going twenty-four hours a day, suddenly, all the limits came off. You could pour all your time into the world and be rewarded for your efforts. And that, all told, becomes wildly intoxicating.

I want to discuss this phenomenon that you’ve described, but first, I’d like to know your thoughts on if and how this could be the foundation of a business. As in, you’ve identified a very strong need from a particular community, and you have the ability to provide for that need. Could you charge a subscription for something like this, and maybe reinvest that capital towards a web portal where a live map as well as player and faction stats could be accessed?

Truthfully, that kind of monetization thinking is neither my focus nor my area of expertise. There’s an old saying that there are basically two kinds of people who work in games: people who create games so they can make some money, and people who make some money so they can create games. I am, for better or worse, in the latter camp. As it was, OVER/UNDER served as marketing for the broader crowdfunding efforts of Mothership Month 25. Would more funding be useful for possible future iterations? Of course. Am I interested in squeezing my players for their money to play? Not particularly.

5. Fair enough. So, with 1,200 players and the 24/7 messaging on the server, managing information flow must have been incredibly challenging. What technological or organizational strategies did you develop to help you track and process the massive amount of interactions happening simultaneously?

The main thing was our Discord bot, Zhenya, named for an NPC AI in A Pound of Flesh. We brought on my good friend ty cobb, an extremely talented programmer and game designer in his own right, who built the bot with a number of features: transferring credits, moving your home location, joining and leaving certain factions, and a few other “default” interactions taht the Denizen players might take. This meant that, at least in theory, Denizens almost never needed to interact with me, Sam, as the Warden—almost everything they could do was handled either by basic text interaction on the server or by Zhenya, leaving me free to deal with the Bosses. For those Bosses, I basically had a spate of spreadsheets to track resources, positioning, and territory, and then a long and complex orders log. As in Cataphracts, the logistics wargame that OVER/UNDER grew out of, I operated on a basic input/output system: several times a day, I’d take orders from Bosses in and add them to my logs. Then, throughout the day, I’d chjeck my logs and dole responses and information out, based on previous orders and occurrences. By the end of the game, each day’s log was often a page or two long, with interactions getting lumped together just to preserve my sanity. Despite all of this, though, I saw very little of the overall game, as it were. There were dozens of active channels and hundreds of active threads, none of which I could actively monitor. I would regularly get pinged by players asking for rulings, advice, or direction, and each time I had to explain that I was coming in with zero context. Because so much of what the players did could occur independent of me as Warden—by design, mainly—it meant that I saw only a very narrow slice of what was happening across the entirety of Prospero’s Dream.

6. In retrospect, do you think Over/Under reveals anything about Mothership as a game or Mothership as a community?

This one’s tricky. On the one hand, OVER/UNDER had relatively little to do with Mothership as a ruleset—neither Denizens nor Bosses had character sheets that resembled the ordinary ones in Mothership, and even the basic modes of interaction were quite far removed. By the end of the game, we were getting people arriving on the server who had literally never even heard of Mothership. On the flipside, OVER/UNDER was specifically set on Prospero’s Dream, and we did a lot of work trying to ensure close parity between the Dream of A Pound of Flesh and the Dream of OVER/UNDER. This included things like physical geometry and the six factions, but also things like tax rates, income, and the basic economic systems at play on the Dream. At the end of the month, nearly every faction in the game was extremely wealthy, and it was quite abnormal for players to deoxygenate and be sent to the Choke—from a game design perspective, the economics were overtuned. It was just too easy for everyone to survive and win, and it was too easy to make money off drugs and guns. All of which suggests, at least to me, that the characters that inhabit the Dream and the other worlds of Mothership are extremely greedy. Many of the sources of income on the Dream are so lucrative that these characters could be doling it out to everyone, for free, and still maintain a lavish lifestyle—but they don’t. “The Company” as a generic entity is rightfully maligned in the Mothership-iverse, but only after OVER/UNDER did I realize the true extent of wealth disparity between the highest classes and the ordinary day-to-day people.

What is next on the horizon for you in terms of game design and implementation?

Art, life, imitation, etc. With any luck, 2026 will be the Year of the Cataphract. I’ve got plans to continue updating the rules, developing the deep-work-in-progress referee’s guide, my own Voreia campaign set, more design diaries, and possibly one or two other things. My main Voreia game’s wrapping up at the end of the year—next year, I plan to run multiple shorter games, likely in the 6–8 week range, try to get more eyeballs onto the project. There are already quite a few people running their own Cataphracts campaigns, which is very exciting, and I’m hoping to inspire and help people to keep doing that, especially veterans from OVER/UNDER. On top of that, I have my usual spate of work: teaching game design classes; freelance editing and graphic design gigs; releasing my latest Mothership project, the space-trucking manual Another Day in Paradise; essays and blogposts on all sorts of topics; and a handful of other projects I can’t yet talk about yet, if only because they might not make it off the cutting-room floor.