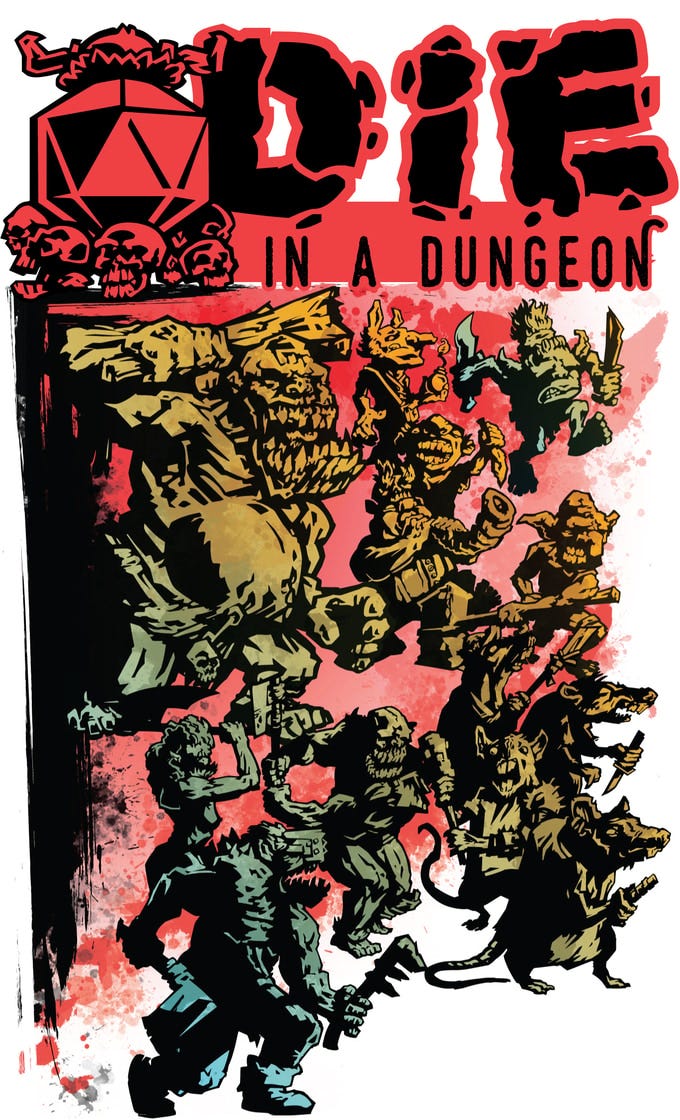

Is today the day you DIE in a Dungeon?

Let's explore the brilliant mechanics behind DUNGENERATOR Decks and DIE in a Dungeon with creator ROLLINKUNZ

DIE in a Dungeon Kickstarter:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/rollinkunz/the-dungenerator-die-in-a-dungeon

Hey Rollin, can you introduce yourself and tell us about your connection to roleplaying games?

Greetings! I go by ROLLINKUNZ online, and I’m an inky illustrator and gonzo game designer!

You may have seen my illustration and graphic design work on ORC BORG (written by Grant Howitt, of Honey Heist / Spire / Heart / etc. fame), ODD GOBS (by John Baltisberger of Madness Heart), or my own DUNGENERATOR decks. Or maybe you’ve seen some cover art of mine floating around on various tabletop modules or video-games!What is Dungenerator?

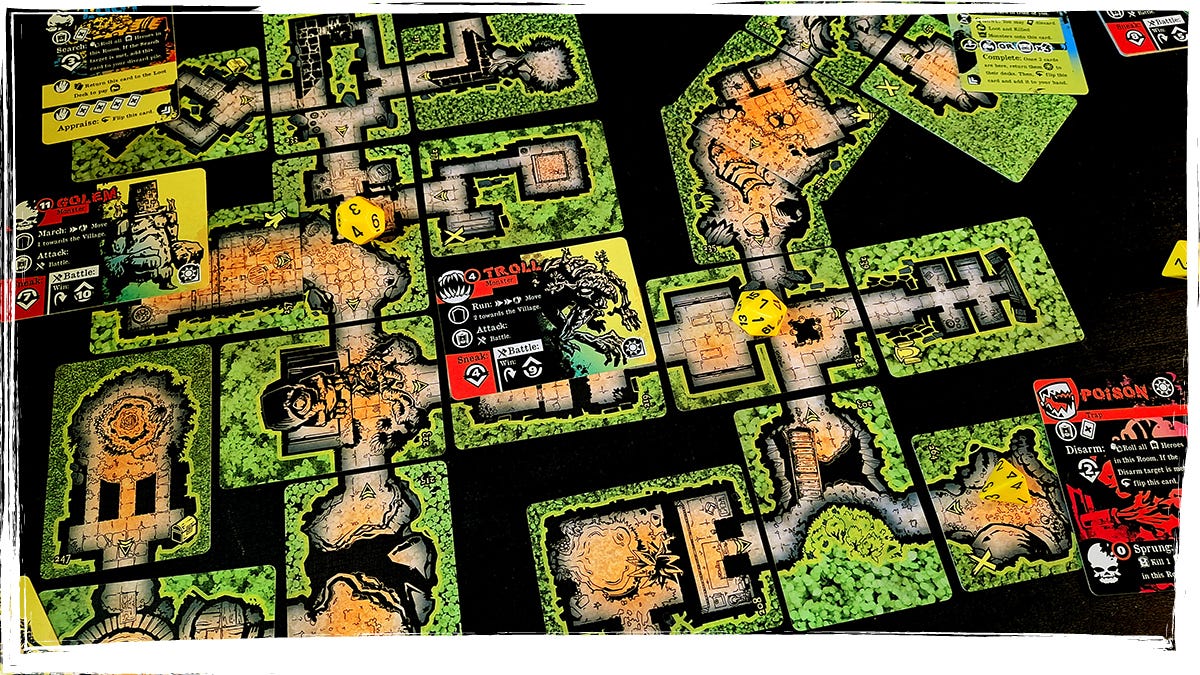

The DUNGENERATOR is a series of card decks that generate inky, organic dungeons! They use a simple double-sided flip-card mechanism I’ve devised to make uniquely twisty layouts, and they’re jam-packed with my own hand-inked art. Two Series have been released so far (a “classic dungeon” theme and a “forest/jungle temple” theme), with (hopefully) a few more on the way!

Let’s talk about Die in a Dungeon. How would you describe it?

DIE in a Dungeon is a solo/cooperative, narrative dungeon-crawler that turns your TTRPG dice into doomed Heroes struggling to protect and rebuild a Village nestled on the edge of a deadly, ever-shifting labyrinth! It’s a massive game that fits in your pocket, uses the DUNGENERATOR decks to generate its dungeons, and is quick to set up and learn. It’s designed to be played as a “filler” game while you wait for the rest of your tabletop party to arrive, or as the main entertainment for an evening!

How did you come up with the idea for a dungeon that continually reshapes itself? It feels like it could lead to endless gameplay opportunities.

The idea of a sentient dungeon couldn’t possibly be new, though I couldn’t tell you where it originated. It’s really just a thematic “skin” for the mechanic of a randomly generated dungeon, which I knew had to be part of DIE in a Dungeon’s design. While developing the solo/cooperative version, I set myself some very particular design constraints:

DIE in a Dungeon would use the DUNGENERATOR decks to generate its dungeons. This would allow me to develop the decks and the game separately (and add variation to the game simply by adding new, thematic dungeon decks), but meant that I was limited to the established format and iconography of the decks.

DIE in a Dungeon would be another use for a tabletop RPG player’s collection of polyhedral dice, and would use no other physical components beyond the cards themselves. This would reduce the complexity of manufacturing and shipping the game significantly, as well as being an excuse for players to go to their local brick-and-mortar game stores or conventions to collect more delicious dice. However, it was an incredible design challenge to remove any sort of cardboard tokens from a game with such a large table footprint/presence!

DIE in a Dungeon must be quick to set up, take down, and play; players should be able to be added and dropped at any point, and any campaign progress must be able to be saved at any point. Because I wanted this to be both a game that one could satisfyingly play for hours on their own or for 20 minutes while waiting for a GM that’s stuck in traffic, its graphic design had to be extremely clear and its game design flexible. Quite a needle to thread!

The concept of building a village while exploring a dangerous dungeon is intriguing. What inspired you to create this blend of settlement building and dungeon crawling?

I needed to include a variety of mechanics that allowed for a player to grow in power naturally over the course of a campaign, and I also wanted to find ways to accentuate the “narrative” part of “narrative dungeon-crawler,” so the Village sprung out of that. Having at least one Hero in the Village allows the player to access a variety of always-available special actions; one per Building. These are verbs like carousing at the tavern, gossiping to find quest rumors at the town hall, pawning your old gear at the junk shop, etc.

A large part of even the most combat-focused TTRPG is the downtime in between dungeon crawls where you have a chat with the local smith and strike a bargain for some new gear, or rest up and relax with your fellow adventurers. This had to be represented! To do this, I leaned into the double-sided “flip card” mechanics established in The DUNGENERATOR decks: Each Building you can potentially add to the Village starts out as a village quest, representing a need that a resident of your Village has. Helping them (by completing the requirements of the quest) ends a session in a victory and lets you flip that card over, converting it into a new Building that you get to add to your Village (and a unique action you can now access).I noticed that the campaign can be played over several sessions. How did you balance the pacing to keep each session engaging without making it feel repetitive?

Great question! While developing DIE in a Dungeon, I played a lot of roguelikes, roguelites, and campaign-focused tabletop games (Gloomhaven, etc.). Each used different strategies to solve the problem of using random generation to create lots of variety while still making new sessions feel unique. One trick I pulled straight from Gloomhaven (and many roguelites) is to keep giving the players new toys to play with; though missions in Gloomhaven usually follow the same general format, the promise of constantly unlocking new, exciting abilities is usually enough to keep players engaged.

The other big lesson to be learned from a game like Gloomhaven is: make each turn interesting! The best “Euro” board games focus on providing difficult, interesting decisions to players every turn, and I endeavored to do the same with my game. Resources are tight, there are many ways to spend them, and doom is almost always imminent!The various Hero types each have a die type assigned to them. Where did you first see or come up with this concept?

I came up with this concept while developing the first draft of DIE in a Dungeon years ago; it was a player-versus-player arena-dungeon-crawler that I shelved before pulling out its dungeon-generating card system to create the DUNGENERATOR decks. I wanted a way to make a player’s set of dice feel like a part of adventurers, and mapping each die type to a heroic archetype accomplishes two things: It personifies them a bit, and it also gives a hint as to what each die will be generally useful for, mechanically. The dice with smaller maximum results (d4s and d6s) are best at sneaking and collecting loot, and the dice with larger maximum results (d12s and d20s) are usually better in a fight. Their archetypes and the game’s mechanics all reflect this.

However, it’s important to note that DIE in a Dungeon is not a game about rolling dice and seeing what happens! Almost all of the mechanics focus on “input randomness” rather than “output randomness,” so you’ll only roll your dice when the game asks you to, and then you’ll decide how best to mitigate and assign the results that you get. (This is another example of that “Euro-game” influence on the design.)I love how players grow their village and heroes over time. How did you approach the design of progression systems to keep players invested across multiple sessions?

There are tons of surprises to be uncovered in this game: Loot that can be appraised to find magical items, villager quests that turn into new Buildings, Gear and actions that can be upgraded, and heroic quests that unlock unique and powerful Hero actions. Even the monsters contain surprises; each acts in a unique manner, and changes its behavior when wounded! My basic strategy when developing all of the upgrades was: cram this game so full of surprises that a player couldn’t possibly see everything in a single campaign. The Hero Quest/Action deck alone contains dozens of options for customizing your deck, and you could feasibly completely ignore it for a campaign and focus entirely on Loot and Gear!

The path your campaign takes will depend on how you want to develop your Village and Heroes (and which Heroes you want to focus on). Though some paths will be faster, as long as you keep playing, your campaign’s story will eventually lead to your glorious victory (and will generate a story that’s uniquely yours)!With the Boss Monster appearing only after key conditions are met, how does this affect the tension and build-up during gameplay?

Though it’s technically possible to defeat the Boss Monster in a single session, it’s ludicrously unlikely. This is a game meant to evoke a narrative of Heroes learning to overcome incredible odds! To that end, the Boss Monster’s arrival is a huge danger for ill-equipped players; it will activate all monsters currently in the dungeon (possibly leading to the Village being overrun or the Heroes all being killed) and will then start summoning extra monsters (possibly leading to the Monster Deck running out and them swarming the countryside). So basically, the Boss Monster accelerates the threat of all of the session loss conditions simultaneously! Players need to manage this (especially early in the campaign) by continuously exploring the dungeon (giving monsters room to spawn and move) and balancing that with collecting Loot, fending off creatures, and completing quests.

Loot can be spent or appraised for powerful Gear—how do players decide when to spend versus appraise, and what was your thought process in balancing these choices?

I’m really pleased with the Loot system. Loot is very valuable as a resource, as it can be removed from your deck to pay for expensive Village actions that might otherwise take a lot of effort (represented by discarding cards from your hand). But Loot also clogs up your deck- carrying too much of it means you’ll draw a bunch of Loot cards on your turn and won’t be able to access your other actions as often! (I think this is an elegant way to represent encumbrance!)

In addition, most of the Loot cards can be flipped over into magical Gear by taking a very high-cost Appraise action. This might take an entire turn, but permanently adds a powerful and unique (but random!) new action to a player’s arsenal. Do you save your Loot to pay for important Resurrections? Do you let a Hero die or a Building be damaged in order to power up your deck for later sessions? Do you try to find ways to make Appraising cheaper, or focus on different upgrade methods? This is the sort of thing I’m talking about when I mention constant interesting decisions!The Dungeon Generator mechanic seems versatile, especially with different deck options. How did you design this to keep the dungeon experience fresh and unpredictable each time?

The DUNGENERATOR decks use a very simple mechanic that I’ve not seen anywhere else: Each card is double-sided, with a map containing Open Passages (leading off the edges of the card) on one side and a Dead End map on the reverse. While generating a dungeon, you simply choose a room, draw a new card for each Open Passage on it, and lay them down. If any of the newly laid cards would overlap another room already in the dungeon, you flip the original room over to its Dead End side instead (and discard the drawn cards). This creates complete, natural, organic-looking dungeons and allows me to use the entirety of a standard playing card for art (instead of making square tiles and grid-based dungeons)!

There’s a unique narrative mode where players can log their village’s history. Did you envision this as a way to add replay value, or is it more about deepening player immersion?

I think all tabletop RPG players are here to create a story. Some people enjoy the extra setup and depth of a solo RPG, which usually takes the form of a journal, and some enjoy cooperatively exploring a world with friends. I’m more in the latter camp, personally, but solo RPGs have always held a sort of unobtainable mystique for me. I love the concept, but it’s difficult for me to give myself time to play them! DIE in a Dungeon is my effort to satisfy both groups. It can be played as a zero-prep dungeon crawl that generates a story, or (with the narrative campaign mode) it can be turned into more of an in-depth journaling session for those that want to come out of a campaign with an artifact of their created world.

The “Trained” version of Basic Actions adds a layer of complexity as heroes level up. How do you prevent this from overwhelming players new to the game?

The graphic design of this game was a massive challenge that took months of iteration. I wanted players to be able to muddle their way through the game without ever looking at the rules, if they wanted! To accomplish this, I added simplified descriptions of basic actions to each of the cards in the players’ starting action decks. Even if a player wanders in from the street and into the middle of a session, they can look at the cards handed to them and figure out their options!

Each session’s end, win or lose, each player is allowed to flip one of these basic action cards to its Trained side, which significantly improves the power and flexibility of that particular card. This, of course, represents the adventuring party gaining experience from their victories or defeats, and is one mechanic that ensures a smooth power curve over the course of a campaign. You’ll only be flipping a single basic action card per session, though, so by the time a few are flipped, you’ll be a veteran!I’m intrigued by the way expansion and secret rooms work—allowing players to control the dungeon’s layout more actively. How does this affect the game’s strategic elements?

Secret Rooms and Expansions are the unique mechanics included with the Series 1 and 2 DUNGENERATOR decks, respectively. Secret Rooms, once placed, connect any and all dungeon rooms that they point to, creating shortcuts through the dungeon (and hiding spots where monsters are unlikely to venture). Expansions enlarge room maps by overlapping two rooms and turning them into one; they were designed to add even more variance and organic flavor to the outdoors-themed Series 2 deck. Both of these can be used to tweak the form of a generated dungeon in the player’s favor, which (like many of the elements of the game) is simultaneously quite powerful and can be fully ignored in favor of exploring other mechanics!

The multiple winning conditions, like completing Village Quests or defeating the Boss Monster, give players flexibility. What was your thought process in providing varied paths to victory?

Really, there are two types of victory in DIE in a Dungeon: completing a Village Quest, which ends the session in a victory for the players, and defeating the Boss Monster, which ends the entire campaign in a victory. Defeating the Boss Monster is a tall order at the beginning of a campaign, so players are given a sandbox-style choice every session: Should they be conservative and attempt a Village Quest to build up resources, should they attempt to take on the final threat of the Boss Monster, or should they ignore both and pursue Loot, Gear, and/or Hero Quests to gain power for later?

This “sandbox” vibe was, I believe, another important must-include element of the design. The promises of a tabletop RPG are cooperation, storytelling, (often) power-fantasy, and agency, and creating as close to an open world as possible through systems and mechanics is important for creating the all-important feeling of agency.The game allows players to drop in or out at any time, which is rare in campaign-based games. How did you design this system without disrupting the flow of gameplay?

This was a goal I wasn’t sure I could accomplish when I began the design! The key was this: The player’s power curve is tied to their deck. All of the actions that a player can unlock that make the game easier to ultimately win are on those cards and the Village Building cards, and those decks can simply be bundled and set aside to preserve a player’s place in their campaign.

In addition, monster actions are tied to each player’s turn (they act after each player), so a single player taking multiple turns in a row versus two players alternating turns doesn’t actually change the power of the forces acting against the player(s). These two design choices added up to players being able to pick up their deck and drop out at any point (or pick up a deck and take the next turn)!The village itself evolves through the addition of new buildings via Village Quests. What were some of your design challenges in making sure these buildings felt meaningful but not overpowered?

Moving all of the different elements of one’s game onto cards suddenly opens a ton of design space- each new card added could alter the game completely, subverting existing mechanics or introducing entirely new ones! The extreme sandbox-y nature of this game, along with its solo/cooperative-only status, meant that I felt free to lean into that without really worrying too much about “balance.” Some cards will unlock unique mechanics or even decks, while others will provide a steady path towards victory. Are some Buildings more powerful than others? No doubt! But (unless you spoil them for yourself) you won’t know which ones, and there are so many in the game that you’re unable to rely upon “what worked” last campaign being obtainable in this one.

The concept of rotating damaged buildings to indicate destruction is simple yet effective. How did you come up with this visual cue for damage in the game?

In short, I had to! I originally had players flip over damaged Buildings, but then I came up with the Village Quest-to-Building progression mechanic, so I had to fit a damaged state somewhere on that single Building layout. Luckily, I was already leaning into the gritty, haphazard graphic design and illustration style you see, so having a big “DAMAGED” slammed across one side of each Building card fit fine.

The game’s art and design contribute to its atmosphere. Where and when did you develop your unique artistic style?

I could talk about this indefinitely, but in short: I got interested in the “shadows-revealing-forms” styles of comic artists like Mike Mignola and Frank Miller at a young age. (I must also give shouts-out to the work of Gabriel Bá and Eduardo Risso, which continued to inspire me as a young artist.) I’ve been illustrating in that sort of style all my life, but until maybe five years ago I was doing so in a very slow, traditional manner- pencils first, figure out where shadows lay, then put down inks, scan, clean up, and add color. Anyway, a few years ago I began experimenting in what I suppose is a more painterly method, using paint markers and sharpies to lay down general forms and then “cutting into” them with corrective tape. That led to me attempting the same method digitally when I picked up an iPad and Procreate, which brings us to the current evolution you see today.

As far as the graphic design goes? I’ve always disliked doing graphic design. I said no to a graphic design degree, and only through necessity did I get back into it (once I picked up game design). But when Rowan, Rook and Decard said yes to my ORC BORG pitch, I told them I could do the graphic design for it as well, and folks seemed to really like it. I found myself enjoying it, too- at least a bit. Being able to consider each spread as its own composition really helped fuel my creative fire. So… that’s what I decided to do with the graphic design for DIE in a Dungeon! There are a bunch of different card types and they all have different layouts (while maintaining some of the same visual language for cohesion). Folks seem to be enjoying the way that’s turned out so far, too, so I guess I’ll keep bumbling my way down this path!Could you see yourself ever creating an expansion of Die in a Dungeon into other themes besides gritty fantasy?

Of course! I already have two or three more DUNGENERATOR decks planned, each with a different theme, so those will automatically expand DIE in a Dungeon as well. If DIE in a Dungeon is successful enough to warrant expansions, I’d love to make whole new sets of Heroes, Monsters, Buildings, and Gear. Gritty sci-fi! Gritty post-apocalypse! Gritty biopunk! Who knows? If people keep wanting this stuff, I’m happy to keep making it.

Links:

DIE in a Dungeon Kickstarter:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/rollinkunz/the-dungenerator-die-in-a-dungeon

More of ROLLINKUNZ’s games:

https://rollinkunz.itch.io/

More of ROLLINKUNZ’s art:

https://linktr.ee/ROLLINKUNZ

I edited the quickstart for this! It's a REALLY exciting project and I can't wait to hold the physical version