Inside Triangle Agency: Where Corporate Horror Meets High-Powered Paranormal

Caleb & Sean Share Their Reality-Warping TTRPG’s Twists and Terrors

Triangle Agency links:

Get Triangle Agency in PDF (DrivethruRPG)

Get Triangle Agency in Print (Amazon)

Get Triangle Agency in Print and PDF (Modiphius)

My full review of Triangle Agency on YouTube

Hi Caleb and Sean, can you introduce yourself and tell us about your connection with tabletop roleplaying games?

Hi! We’re Caleb Zane Huett and Sean Ireland, the designers of Triangle Agency. We met as counselors for an afterschool program that ran tabletop RPGs and board games for kids, then both became professional GMs after that. We both have backgrounds in theatrical performance, writing, and production–and have played TTRPGs and TTRPG-adjacent games basically our whole lives.

Caleb is also an author of novels for kids. (Triangle Agency is his first major work aimed at adults.)

Sean is also a theatrical writer and producer, and has had past lives giving tours at the Met, teaching computer science to kids, and working in HR for a startup.

What is Triangle Agency and where did it come from?

Triangle Agency is a TTRPG of paranormal investigation and corporate horror. It’s also a big, 300-page book that’s written to be entirely in-universe. We think it’s fun to read even if you aren’t playing!

The system is new, and plays a lot with the line of what’s “in” and “out” of the game. Players take on the role of Field Agents with huge, reality warping power–but they’re in a system that’s asking them to do emotionally difficult and personally restrictive work. The game came from Caleb making a logo for fun while thinking about a paranormal investigation game, and then a few days of intense brainstorming later we had a concept we thought could really work. Seems like we were mostly right!

What are some of the biggest lessons learned from the crowdfunding process for Triangle Agency?

We got really lucky, and have not had any really major issues! The main lesson is that everything takes longer than you think it’s going to take, from writing the book to shipping the game. Our backers have been very generous with us, though.

Okay, I want to dig in a little bit and ask you some critical questions about this game. First, I DO like the neat, tidy, almost symmetrical mathematics of the dice system, but I also hate the shape of the traditional tetrahedron d4. They’re hard to pick up and they don’t give much satisfaction when rolling. What are your thoughts on the physicality of the d4 and the fact that they are used for about 98% of this game’s rolls?

The Agency hasn’t liked how we answered this question in the past, so we’ll say exactly what they’ve told us to: “Thank you so much for this opportunity to remind players that the d4 is flawless, and mandatory for playing Triangle Agency. Any attempts to circumvent use of the d4 will be met with a swift response from your supervisor.”

The core rulebook is absolutely riddled with cheeky jokes and humor. The humor lands for me personally, but sometimes the jokey stuff takes up half a page, or even a whole page. Did you ever consider presenting a more straightforward rules presentation that didn’t devote so much real estate to humor?

No, there was never a chance that stuff would be removed! The humor and storytelling in the book are not “decorations” for the game; they are part of the game. A huge part of playing Triangle Agency is negotiation with the rules, and choosing whether to believe what they tell you is true–the comedy is part of that. Is it a trick? Is the Agency disguising a truth by making you think it’s unserious? Our game is also not a broad system for any kind of play–it’s a specific system for a specific game, and reading the book first is how you get the result we’re looking for.

Also regarding layout, I felt like the book went in two aesthetic directions at once: on one hand you have a sort of in-world corporate manual (Tim Denee’s Deathmatch Island is the best example I can think of), but on the other there are more traditional illustrations of people, creatures and other things. How did you decide to take both approaches for the book?

On the art side, each artist was given control over a particular part of Triangle Agency’s world. We have Nathan Rhodes doing traditional ink illustrations (the figures with the triangle heads) to show how the Agency brands itself; Kanesha Bryant’s incredible monster designs for the Anomalies and “rebellious” side of the game world; and G.C. Houle and Ryan Kingdom working together on the “real world.” Each is united with color and tied to a specific theme. This way, each section has its own identity! Then we have Kodasea and Corviday doing large, fully-illustrated pieces to show you a glimpse into a fully realized, kinetic game world.

For layout, we wanted to frame the text and illustrations with the feel of a “real” corporate manual. I worked with Michael Shillingburg and Ben Mansky to design something clean and modern that we could break and twist as the storytelling of the game got more complicated.

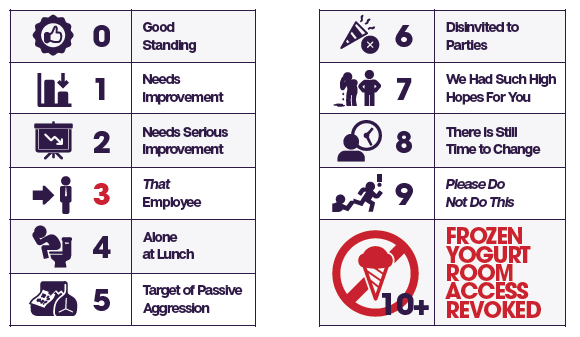

Regarding jokes, there are spots where there could have been substantive mechanics or rules, but instead there is essentially a jokey table or list. The prime example of this is Agency Standing, which ranges from 0 to 10+. All of the entries for this seem tongue-in-cheek. What went behind the choice for making the demerits track humorous rather than having narrative or mechanical bite?

The truth is, very little in this game is “just a joke.” The humor of this table is an introduction to deeper mechanics. The Agency doesn’t want you to accrue demerits, so they start here with a shaming strategy that seems funny because to many players it feels meaningless. What demerits actually represent–and how the Agency actually punishes you for failing to respond to their shaming strategy–becomes apparent as your character continues their career. In this moment we’re doing two things: pushing players to understand that getting a few Demerits isn’t the end of the world, and setting up that the Agency is a place that feels “gentle” until they decide you’re no longer valuable to them.

Also, this table does have narrative bite, even taken at face value. One of the top three questions we get is whether it’s possible to get frozen yogurt privileges back by “removing” demerits. (It’s not.)

The game is humorous in its presentation but also in how it is intended to be played. In my experience, sometimes the harder people try to be funny at the table, the more painful and unfunny it can be (whereas if humor is not the main objective, when it does come up it is often pretty memorable). What has been your experience with people trying to be funny at the table when playing this game?

How the book feels is not supposed to be identical to how the gameplay feels. Triangle Agency is a horror game that communicates through comedy, and we think the best results come from taking the world seriously and letting comedy arise when it’s appropriate. Some of our favorite stuff in the game comes from the tension of things being funny right up until they can’t be anymore.

In the game your characters are meant to be agents answering at some level to a local Branch of the agency. What kind of fun stuff have you seen tables come up with for their local Branch, and do you think there could have been more guidance in the book for how to design or generate a Branch?

Some of the coolest stuff we’ve seen comes from people taking our first recommendation, which is to play the game in a real place! The game benefits a lot from genuine affection for, and knowledge of, the setting you’re playing in–so we recommend playing in your hometown, or a place you know a lot about from travel. Maybe we’ll have more tools later, but our “official” setting, Ternion City, is largely undefined on purpose. The game’s core mechanic involves redesigning the world around you by changing history, so too many details would be too quickly overwritten. If people want some extra setting details, though, our book of missions The Vault is all set in Ternion City and fleshes out 12 distinct neighborhoods and suburbs.

Your character’s anomaly is a specific set of powers that they can roll to achieve, and with each power there are three possibilities: Success, Extra Successes and Failure. I noticed that some of these powers have way more impact on a target than others. For example, We’ve Got Time, under the Anomaly of Timepiece, says that on a success that whatever task is focused on and approached genuinely will be completed on time. Which could be huge narratively, maybe too much so. And the Gun>Eliminate power is even more insane. But other powers just distract an NPC for a short period, etc. How does this imbalance of narrative impact for each power play out at the table for you?

My favorite part of this question (which we get a lot) is that every person who asks it mentions different Anomalies. They’re all “overpowered,” and the limitations of each are more about which kind of creative thinking you prefer to do. Missions in Triangle Agency are not often difficult to complete–you were hired because you have these incredible abilities, you can resurrect immediately upon death, and you can change history to improve your situation. Ultimately, over a campaign, you’re supposed to be thinking about why you’re completing these missions at all. If you can stop time to complete any task, why are you catching Anomalies? Why aren’t you using that power to do something else? The game’s about getting to those questions. It’s not a tactical game; “balance” is a less important detail here.

Each character has a “Reality,” which is like their real-life job or existence that they should tend to when not hunting or cleaning up after Anomalies. Reality Triggers can add up to the point that your character has to switch “Realities,” but there is no real mechanical consequence to filling up a Reality Trigger track. You just sort of fill it up and change roles. Why did you decide to make these tracks so relatively anti-climactic, or am I missing something here?

The situations you’re describing are losing your child’s trust permanently, losing your job, losing your sense of purpose, finally finding a true love, and getting caught by the people who have been trying to kill you. If you’re taking your characters seriously, too much mechanical baggage will make these situations less meaningful, not more.

In play, too, the Reality needs to be the easiest to shift around–we’ve found it’s the thing players are most likely to want to change over the course of a career, and it’s defined by a specific set of circumstances. If the Struggling (who is defined by being broke) comes into a lot of money due to story circumstances, we don’t want to get in the way of your characters growing.

The game encourages narrating the “Reality” scenes where players try to nurture connections with other people in their normal daily lives, and there are relationship tracks to assess connection strength and quality. But are there enough mechanics there to warrant anything more than a few minutes of shared narration? What does one of these interlude phases look like at the table and how long do they typically last?

The Reality track is designed to encourage (and is very explicit about being for) people who like free-form roleplay. The powers you earn from it also involve the effects and characters of free-form roleplay gaining mechanical power. If you don’t like scenes like that, you don’t level into Reality!

Time-wise, we have some folks who do multiple sessions meticulously moving through their scenes, and some who do it quickly in fifteen or so minutes after the mission is complete.

What is it like for players to reach the end of their character’s career at the 10- to 30-mission point? Do the relationships and connections make the character substantial, or does the accumulated weight of all the weirdness and jokes make the character easy to let go?

It’s different for everybody, and their relationship to their character. If you’re asking “is it good?” we think so!

There’s a whole “requisition” system in the game where you can buy a handful of different items using Commendations that you earn over the course of play. But there are only 11 items listed in the book (and one provided for each character job archetype). Does the requisitions purchasing system get used a lot in actual play, and do GMs often have to come up with their own?

Investing in your Competency unlocks more stuff to purchase, and there’s an explicit path to your branch designing more that’s unlocked very early in the game. It’s intended to be collaborative, between the GM and the players. They’re used a lot by the characters who invest into Competency!

The GM section of the book is a solid 60 pages of game-specific advice and guidance, but it is extremely avante garde in its layout and presentation. I know there are admirers of this GM section, which features a persistent NPC persona and an emerging meta-narrative all its own. But have you gotten any gripes about the aesthetic choice for this chapter?

No gripes, just requests for something that’s easier to read for particular folks–which is coming! Our accessibility update got delayed by a few months, but it’s still on the way.

There are these so-called Playwalled Documents that occupy a third of the book and contain all kinds of fun rules variations and mechanics that might have been great to include in the rules section of the game. I can understand relegating them to one-off occurrences, but is there a chance that some or many of these Playwalled entries never get evoked or read by a group?

They are in the “rules section” of the game! The whole game is rules. The documents you’re referring to are specific ways characters “level up” in our game, and they’re organized this way so there’s mystery and joy in discovering them as you play. You also can just read them by following the codes down particular tracks, if you’re interested in seeing how they develop, and lots of people do.

As for whether every group will see them–absolutely not! There are over 200 abilities in this game split among the character choices, and another 30 or so entries that come from how characters spend Time. Every game is supposed to be different, just like how you don’t see every power of every class in any single campaign of a game.

Regarding these hundreds of wildly imaginative and creative Playwalled entries, is your imagination exhausted to any degree? Is there any more ground you could even cover here?

Yeah, we could probably make another thousand of these. Many of our players have! They’re super powers, story hooks, infinitely variable. Triangle Agency powers are about manipulating fiction in interesting ways, so if fiction can still do new stuff, we can too.

A lot of the game seems structured around offloading GM responsibilities onto either the players (e.g. coming up with their Reality NPCs or via the Ask the Agency mechanic), or onto the book itself by referring to Playwalled Documents. What are your thoughts on those more traditional responsibilities of a gamemaster that are avoided in this game?

This one is probably best answered by playing the game to see how it works, but: in general, the GM’s job in Triangle Agency is hard. Players have huge powers that can shift the direction a mission is going in an instant. GMs are asked to be pretty thoughtful about creating narrative consequences for big choices, and if they were also playing every character and designing the entire world, it wouldn’t be tenable.

Plus, the stuff we give to players (playing major NPCs in other people’s lives, rewriting history to change setting details) is fun, and creates a style of play that emphasizes everyone’s input, rather than a world built by the GM alone for players to move through. It’s a style of play we really like, and love to see in other games, too.

Okay, enough pestering you guys. Tell us about the Triangle Agency community and what you’ve seen in terms of third party publications and resources that they have created so far.

The biggest gift the community has given us is tools to make character management easier–a lot of folks who like TA are also very good with spreadsheets, it turns out, and virtual tabletops. (You can find some great ones on our discord, discord.hauntedtable.games!) There have also been a few larger projects adding character options to the game (we recommend checking out the Amaranth Folder on itch.io).

Another great thing is our community working together to build missions on that Discord server–every day or so another GM is bringing the seed of an idea and the crew there works with them to develop it out into a full mission. It’s so fun to watch!

Finally, this year we’re hoping to have a game jam for the community to come together and build Anomaly Retrieval Missions, but we’ve been delaying that as we figure out a more streamlined way to structure them. A huge project of our current year is learning how to make additional content in a more digestible way.

What are you planning for the future of Triangle Agency?

There are a few promises from our campaign that are incoming–most especially, a solo game by Alfred Valley about working inside the Agency’s Anomaly Vault, and a module for FIST written by its creator, B. Everett Dutton, where you can play as FIST Agents fighting against the Agency at a key point in its history.

Other than those, we’re focused entirely on support right now. Several folks are working on new missions, and we’re testing new ways to onboard players. Eventually we’ll probably do some other large projects in the Triangle Agency world, but there’s been so much love for the game that we want to give it a stable ground before we move on.

Thanks so much for having us!

Triangle Agency links:

Get Triangle Agency in PDF (DrivethruRPG)

Get Triangle Agency in Print (Amazon)

Get Triangle Agency in Print and PDF (Modiphius)

My full review of Triangle Agency on YouTube