D&D Isn’t Enough: Why Grimwild Fills a Gap in Heroic Fantasy RPGs

J.D. Maxwell Explains His Revolutionary Take on Mid-Crunch Narrative Play

Grimwild links:

Grimwild Free Version (DrivethruRPG)

Grimwild Full Version (DrivethruRPG)

My Quick Look video on Grimwild

Hey J.D., can you introduce yourself to us and tell us about your connection to roleplaying games?

Hey, my name’s J.D., but most people call me Max. My background isn’t all that flashy—I worked as a layout designer a few big companies for a long time until I was laid off during a round of cutbacks over a year ago. That turned out to be a great excuse to dive into game design full-time, and here we are.

I’ve been playing since university in the early 2000s and really got into Burning Wheel when it first came out. Until about 2015, I only gamed occasionally, but picked the hobby back up in earnest, diving into more narrative games around that period like Dungeon World and a bit later Blades in the Dark. It was around that time I started collecting and have a pretty nice collection of physical books these days, which I’m always looking to add onto.

I think it was the collection aspect which first got the idea that I should make a game into my head. I saw many small publishers putting out high quality books and started looking into the manufacturing side of it myself, and quickly realized there was a wealth of options available if you could get even a 500 copy print run together.

When did you start working on Grimwild and why did that come about?

The foundation for Moxie—the system behind Grimwild—started taking shape in mid-2023. It began as a small, unreleased sci-fi zine game—a way to test ideas. I’d been playing a lot of Blades in the Dark for years, which came close to what I wanted but didn’t quite hit the mark. We’d often finish off sessions and they felt like they fell a bit flat, but when we looked back on it, the story we told actually flowed really well and felt quite dramatic.

I started wondering what was going on with that and realized a lot about how my group accessing the meta-channel so much during play was killing the flow of the story in my own imagination. I love cinematic storytelling—thinking about “camera angles,” soundtrack cues, and scene subtitles while playing. BitD captures some of that with its writer’s room approach, but I wanted something more improvisational. On the other end of that, systems like Fate have a great flow, but lack the level of crunch that I like. Then you have something like Cortex which manages to have lots of knobs and dials, fiddly bits, but doesn’t capture the right flow for me.

This got me thinking back to Burning Wheel and how Beliefs, Traits, and Instincts act as a very convenient communicator of meta-information about your character, getting players on the same page about each other, and meta-currencies helping push play along as well. This started clicking in my head and I began designing Moxie to integrate those concepts.

After the zine, I built a weird west-like game called The Wild Frontier of Venture. That game is part of my larger plan, to release a series of 7 games all within the same planetary system - connected by both fiction and system, but each a separate game.

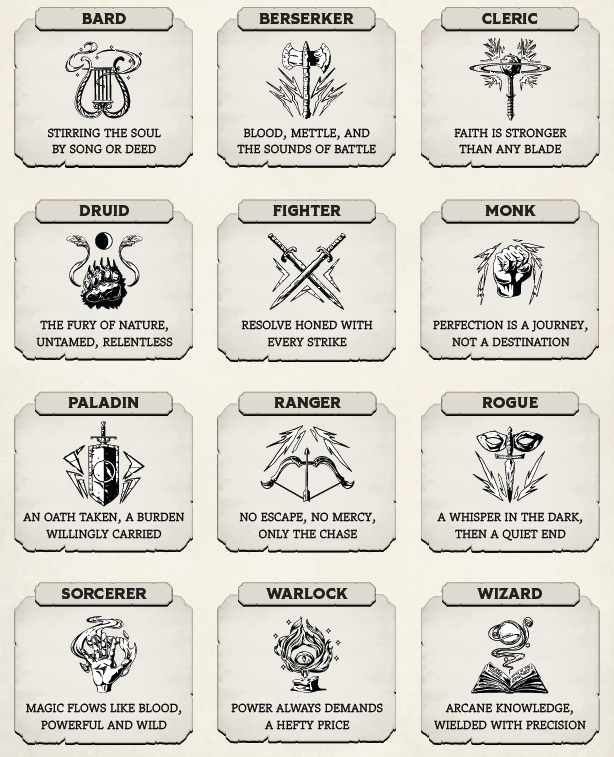

After finishing that first game though, I felt a bit unsatisfied still and wanted to put Moxie through something of a stress test to see how versatile it was. That’s when work on Grimwild began. Heroic fantasy is an underserved genre in mid-crunch narrative games, and I like that generic fantasy flavor of D&D, so I wanted to make something along those lines. It also lets me push the power level of the system, and the 14 character classes each with 8 talents gave a pretty wide breadth for testing. Grimwild also allowed me to focus entirely on mechanics, leaving the setting implied by the system and otherwise up to the players to decide at each table.

Now that Grimwild is complete, I’ve returned to Venture with my creative partner, illustrator Per Janke, for a full rewrite.

What was your rationale for releasing so much of Grimwild for free (140 pages for the free version, 174 pages for the full version) as well as all of it under a CC BY 4.0 license?

Kevin Crawford's “Without Numbers” model inspired me—it's easier to recommend a game when there's a free version everyone can access. I've always liked the idea of community copies, but I prefer removing the limits altogether. This way, anyone can get the rules without barriers, and it also makes sharing them with your group simple. In the end, the free version helps out sales as well as long as the free version is impressive enough (and not lacking) to leave people wanting more and to support the creator. That's the key.

The CC BY 4.0 license was an even bigger deal for me. I love the idea of people remixing, reworking, or building on my games. I enjoy working on my own, outside of a team, but I also enjoy having other people building things around me and tossing ideas around. By helping create that kind of environment, I get the freedom to work as I please, but the collaborative satisfaction of working around others. During development of Grimwild, the Discord community gave an immense amount of feedback, round after round of pouring over the classes and talents. Now we're seeing fan-made supplements and full game hacks getting started, which is great to see.

And while it might not be live yet when you read this, we're launching our SRD and an online supplement library at Moxietoolkit.com soon.

Alright, here’s where I’m going to start throwing all of my questions and concerns about the game at you. You introduce a lot of new terms for familiar RPG concepts. Why replace existing terminology with your own? Also, the core rules are just 22 pages but packed with novel mechanics—how do you address concerns that this might overwhelm new players?

Two reasons: First, to avoid baggage. Familiar terms can come with assumptions that don’t match how the mechanics work. For example, my diminishing pools aren’t quite Forged in the Dark clocks, so calling them clocks will probably cause confusion. Tangles don’t work exactly like compels in Fate, and I always felt the term "compels" was a bit off anyway.

Second, Grimwild is just the beginning for Moxie. With the series I’m working on and other “Made with Moxie” games being created, establishing a unique lexicon creates a shared ecosystem for players and designers. Terms like “thorns” feel intuitive and identifiable within Moxie while being distinct enough to avoid direct comparisons with similar mechanics from other systems.

As much jargon as there is, I think you’d be surprised how quickly it settles into the vernacular of the community. And when that happens, I no longer have to worry about ambiguity—they become our terms that the community shares. A few egregious examples might have slipped through, like my bullishness on saying “path” instead of “class,” though even those are rooted in the fact that later games will have different character creation systems, and I want the terminology to flow smoothly. Venture itself is built on a lifepath system, while its follow-up dieselpunk mech game, Prosperity, uses paths for PCs and class for the type of mech you pilot.

A final example I can give revolves around the roll results, which use unique terms for their names. A high roll of 1-3 is called “grim,” a 4-5 is “messy,” and a 6 is “perfect.” It might be easy to think that I should have used failure/partial success/success for this, but the troublemaker is really the term “partial success.” On a 4-5, you accomplish what you set out to do; it’s just that something else went wrong. There’s a strong prevalence, I think, in games with partial successes (often also called mixed successes) for players to feel that a 4-5/partial is a failure. I’ve hated the terminology surrounding that 4-5 roll for a very long time. That’s where "messy" comes in. Messy isn’t failure. Messy isn’t halfway. Messy gets the job done—it’s just messy! Some consequences come along with it. So once that was set as messy, I wanted the other words to jive with that feeling, too. If you roll a failure, I want the GM to hit you hard, appropriate for the situation, but not pulling any punches. The result? Grim. Expect the worst. And if a 4-5 is messy, that makes a 6 perfect. It’s clean. These slight naming changes have subtle effects that ripple throughout tabletalk and how the rolls themselves are perceived.

To answer the second part of your question, I designed Grimwild with experienced RPG groups in mind, trusting GMs and players to find their own rhythm with the game. While the rules are concise, the game is designed to spark creativity rather than prescribe every detail. The text assumes you’ll experiment and adapt, which some groups love, though others might find daunting. For those seeking more structure, I’d recommend leaning on the examples and optional rules provided, like token-based initiative. But I’ve got to be honest, really. I wrote the rules for myself, for how I like reading books. That’s my design philosophy—make games for me and hope other people like those kinds of games. They might not be for everyone, but for me, they feel right.

Diminishing pools may be my favorite tool of the game, where timers, dangers, tasks and resources all tick down with diminishing dice pools (the d6s are discarded if a 1-3 is rolled). But the swinginess of this is undeniable compared to a trusty Clock. In your experience, have you ever seen one of these dice pools deplete way too quickly or take too long to deplete?

Sure, that happens sometimes, but it’s a feature, not a bug. If you don’t want the possibility of swinginess, you should pace with another technique. You don’t have to rely on pools to pace timing; you do it when you want to create dramatic tension. That’s the key to them—and most mechanics in the game. They’re drama generators.

One point of friction that did arise during playtesting was the tenaciousness of that final die being a 50/50 coin flip. That led to mechanics to alleviate that. When a die isn’t dropped even though you made effort towards it, you instead gain a secondary effect—the big bad guy is pushed back, and some minions are taken out instead, or they lose a powerful option that was available to them before, like spellcasting. Again we see it: drama generators. And if you roll 1d and it doesn’t drop, you can also push yourself—take damage to your character to drop that last die, representing that final heroic effort and sacrifice if you’re willing to go for it.

Story points are a powerful metacurrency in the game where both GM and players can spend to add substantive details to a scene. The book doesn’t offer many examples of this and you even admit that there are gray zones between set dressing, acceptable story details and those that are too impactful to be admissible for a Story point spend. How is a GM supposed to walk this line when running the game?

I think that’s up to the GM to decide. You’ll probably notice that the game, in general, is fairly light on examples, and the rules are quite terse. I like to assume quite a bit of GM competency and knowledge of roleplaying games, as I previously mentioned.

I know that most games try to teach from the ground up, but I really admire games like 2400 that just lay the rules out and let you do with them what you will. From people picking up and running Grimwild, I’ve seen pretty much the same amount of problems and questions about the rules that you see with any other game, so in practice, I feel like it’s worked out fine.

As for where to draw that line between player agency and the GM’s territory, I’m not all that interested in defining it. I lay out some basic ground rules; then it’s up to every group to figure out where those lines are together. At some point in development, I wrote up an exhaustive amount of examples of these and felt like it really just served to handcuff creativity and group freedom rather than enabling it.

This kind of circles back around to me writing the game for me—I often feel like rules can be a bit too prescriptive, ingraining a need to pull them out and reference them in play. Moxie is meant to be internalized, and when you forget a rule, you make a judgment call or story roll to keep the pace flowing. It’s built as a series of nets, with the uppermost being quite specific rules and the bottommost (story rolls) being broad, but there’s always something that can catch whatever the fiction is throwing at it.

Why did you decide that players have the final say on long-term and permanent conditions? I understand the intent maybe, but isn’t there the risk of players being overprotective of their characters?

It’s just not that kind of game. You’re either going to lean into the drama or you’ll find a different game, I think. Long-term and permanent conditions strongly affect how you roleplay a character, which you might spend the next several months doing. Having no choice in that just seems bizarre to me. I think perhaps it’s the opposite, actually—unless the theme of a game is specifically about awful things happening to a character, why wouldn’t the player always have the last call on such things?

But in actuality, I think GMs in most cases wouldn’t make such a drastic call in a game anyway without checking in with the player. When was the last time one of your character’s arms was ripped off without your okay? And even if it was, I bet it was probably coming from a chart—letting the GM disclaim responsibility there, and the usage of such a chart being agreed upon with the game choice. By putting this rule in the book, it codifies it and empowers the GM to hit really hard. Now they can more easily go right for the tough consequences because they know that players know they can say no.

Grimwild’s magic uses magnitudes and themes. Do players actually invent new spells on the spot, and once created, can they cast them repeatedly? How do you handle balance and tracking?

This is a pretty well-tested system, really, from Barbarians of Lemuria and later The Electrum Archive, with some Maze Rats thrown into the mix as well. Grimwild just builds on those. In practice, it works very smoothly, and I’m not just saying that. It’s many people’s favorite part of the game.

You compare spells against what a normal action roll can accomplish (or equivalent narrative impact), which is generally easy. Then the themes act as both permissions and limitations. So when they use magic, they don’t exactly “create a spell”—they think about what they want to accomplish, look at the permissions and limitations given to them, and then declare what they’re trying to do. Using a fire spell to melt a lock is no different than using a hammer to smash it. If you had shadow magic or a bow, you probably don’t have permission to attempt that.

I appreciate the brevity of every component of the book, including the format of a challenge. But honestly, some of the challenge blocks leave me a little bit cross-eyed. Could you break down what this Boarding a Pirate Ship challenge entails and how it would actually be used at the table?

I think that, if there’s one failing of the book, it’s that it doesn't let people know that these challenge blocks and linked challenge examples are just that—examples. Even more than examples, they’re kind of like my own GM scribblings. They look a bit more formal than they’re meant to be.

I’ll unpack this challenge block for us, though. Once you get used to it, it flows easier. It’s laid out in the rules before this briefly, but at the top, we have a simple name: Boarding a Pirate Ship. Features are a few truths about the situation likely to affect the conflict. By writing these down, we remember to bring them into play regularly and have them affecting relevant actions.

For threats, the 4d Waves Crashing is a timer pool. When all of the dice have been dropped from it, waves crash over the ships, and the GM can make an impact move—likely knocking everyone to their feet, forcing defense rolls. This will affect the enemies as well, of course. For added fun, we can make that pool repeating.

The other threat here is Kraken Tentacles. We have to imagine this scenario and ask why they’re there. This is just an example, and when boarding a pirate ship, why would there be kraken tentacles? Maybe it’s just a kraken’s hunting grounds. Maybe it’s been summoned by the pirates. Maybe they have it held captive. Regardless, these kinds of threats have two bonus suspense (the small circles), a metacurrency the GM can spend to hit the PCs with moves.

Down below are the soldiers. We have an abstract 4d pool of Deckhands. We don’t know, nor need to know, the exact number. They’re Mook Soldiers—this is their tier and role, a structure GMs can use to help create differing power levels of enemies. The deckhands are a vague group of some deckhands. At 0d, they’re wiped out—you knock that pool down with aggressive actions towards them, or maybe the waves from above knock some over the side as well. Below that are similar archers, but these have the Marksmen role. The roles inform what they’re likely to do in combat.

Three Swashbucklers, without any kind of pool attached, just represent three distinct enemies. Each probably takes an action roll to take out—their tier is “tough,” defined in the rules as being about an action roll’s worth of effort to deal with. Finally, below that is a Pirate Captain, a 4d challenge. Challenges give extra bonus suspense to spend on moves, and the 4d pool means they have quite a bit of tenacity in the scene. The captain’s role is an overseer, so they’re just as likely to spend those impact moves commanding or rallying troops as they are attacking the PCs.

Now, I think the scene comes into view a little bit better once we get used to parsing this information. When used to it, it gives you a dynamic scene ready to play out, of waves crashing into the ship and kraken tentacles flying wildly while you mow down archers and deckhands before facing off with the three tougher swashbucklers. All the while, the captain is meddling in your plans by issuing orders and countering your tactics.

This example uses pirates because it’s relatively easy to map the pirates to the mechanics. You probably don’t even need to write out this block, actually. But let’s imagine that they’re instead going to fight the Ochre Jelly king.

—-----------------------

Features: Sticky, slimy floors; hazy fumes

Threats: 4d Toxic Fume Clouds; OO Spawning Ooze Tendrils

4d Gelatinous Broodlings (Mook Swarmers)

4d Slime Gushers (Mook Marksmen)

3 Morphing Oozepods (Tough Tricksters)

4d | Ooze King (Elite Skirmisher)

—-----------------------

Once most of this clicks—and probably not in the first read-through or even in the first session—but once it clicks, you can get the whole combat dynamic at a glance at a small block. That’s what I like as a GM, and that’s what my notes look like. Here we get the picture of the Ooze King and his three oozepods using trickery and hit-and-run tactics while the broodlings swarm the PCs and gushers rain down slime, all set against the backdrop of the highly volatile environment also out to get them.

Combat rules span just one page, with no turn order. You just “map the fiction” like any scene. For D&D-style players used to full combat chapters, how do they adapt, and have you seen any drawbacks?

You have two types of players, ones that dive right into it and enjoy the freedom and those that struggle a bit looking for the buttons to press. Positive encouragement to think within the fiction, to ignore their sheet, and just do what their character would do next is effective.

But what I find most refreshing is that play, even with those players, flows nicely between combat-style beats and non-combat style beats very smoothly. They might struggle to know what to do or when to act during a combat, but the beats can flow between swinging a sword, holding a door shut, jumping out a window, a mad scramble wrestling on the ground, and running away without any stop in our flow. The players that seem to even struggle with the system get swept right along with that flow no problem at all. In retrospect, especially after pointed out, it hammers home the benefits of such a system.

At other times, you’ll see struggles with this that are more based on player dynamics issues. Some people don’t feel comfortable grabbing the spotlight, while others accidentally hog it without realizing it. I think the GM can do a lot towards easing that out, as can the other players, but I also included a write-up on token initiative for groups that really feel like they need more structure. Each player gets 2 tokens and you spend 1 each time you act. When everyone’s out of tokens, it starts over. You can even use this in any kind of zoomed-in sequence, not just combats. Easy-peasy.

Factions are meant to be tracked off-screen by the GM in terms of their resources and their goals. You say in the book to “keep four to six active factions, balancing major and minor ones, with competing goals.” How is a GM supposed to juggle that much information and convey it to players without overwhelming themselves and the players?

Factions are mostly tracked between sessions, acting as reminders for the GM that the world should keep moving along and remain dynamic. But more than that, they’re also a way for the GM to disclaim decision making and enjoy watching the emergent story develop. I like the GM to be playing the game, too, and to be surprised by what happens. By putting the goals on timers like this, you never know which ones are going to run out first and where the story is going to go. For me as a GM, that’s really fun.

About balancing the workload, I think it’s no more work (and often less) than the GM would have been doing anyway. It’s just a structure that you can offload some creative ideas on and then watch count down. Then you bring that into the next session. You don’t have to worry about thinking up what the world did, just jot down new faction timers as they pop up in your mind or during the game. They also make for wonderful consequences to hit your players’ goals with.

Each character path (i.e. the 12 core D&D 5e classes) has seven Talents that players unlock by playing through sessions and gaining XP. In your experience, has this relatively lower selection of talents affected re-playability?

Including the 2 in the last Extras chapter of the book, there’s 14 paths, each with a core talent and 7 additional related talents. The important point is that you can take talents outside of your path without any limit or penalty. The paths are really just the core talent, and then a thematic collection. The only limit is that you can’t take another core talent, as they’re uniquely powerful. So that gives you a total of 98 talents to choose from.

In the exploration phase of the game, in which players and GMs spend Exploration Tokens to add details to the map, players can earn Spark metapoints by basically talking about their environment or looking around. Doesn’t it seem a little too easy to generate Spark here, even unintentionally? Is there such a think as too much Spark?

There’s a few things going on here that I want to mention. First is that you’re limited to a max of 2 spark. So you can’t pile it up endlessly. Also, the exploration section is an optional part of the game, a kind of subsystem to add on for exploration-heavy campaigns.

But the main thing is that it is easy to gain spark. All you have to do is give a poignant scene involving the world you’re exploring. But the thing is, without that, players rarely take the time to give such scenes. There’s a kind of social pressure to keep the game moving towards

These scenes are also self-policing in the end. People enjoy getting metapoints and describing nature, but they themselves want to move on and do something action related. In practice, it gets used once in a while when people have a good idea.

This is a lesson I’ve learned from Belonging Outside Belonging games, where you earn tokens by doing specific actions. It’s the entire flow of gameplay there and all you have to do is say that you do one of the triggers to get a token, which you can then spend later to succeed at doing something you want. And it just works, because more often than not, people just grab tokens when they have a good scene in mind. The balance really is creativity, screen time, and social expectations. Grimwild specifically tells you not to play to win, but to play to tell a good story. If the ease of generating spark is too tempting instead of being a reward for taking the time to give a vignette about the joy of nature, the game might not be a good fit.

Spark in general is like this. You get it for “sub-optimal” play, both in regards to efficiency, game time, or screen time. You get to play selfish, and the mechanical reward makes everyone else at the table okay with it because they know they’ll get their time, too. The spark being rewarded is as much for the other players’ benefit as it is for the one receiving it.

The monster blocks, like everything else in the book, are titrated down to a zero-fluff essence of the soul of each beast. But I wonder if the GM has to do some of the heavy lifting here in order to get the monster ready for a scene. What additional details are generally required before one of these monsters is usable in a session?

Once you’ve internalized how challenges work and can set them up in your head without prep, or become able to jot down a few traits and moves off the top of your head before a particularly big fight, monsters are easy to run. Actually, the monster blocks themselves are less about running the monster in a fight and more about giving some fiction to add surrounding the monster. Sure, they cover typical moves they make, but most of the entry is concerned with giving them motivations, plot hooks, and to add sensory details around them to breathe life into the scenes.

I’m a zero-prep GM generally, or sometimes use the very light prep style I laid out in the Fiction Pillars section in the back of the book. The book is made with that style in mind.

I have a similar concern about the “story kits,” those one-page scenarios that give you a ton of loosely connected ideas centered around a main story premise. How much GM prep is required in order to get one of these kits ready to run for a session?

Like monsters, it all depends on the GM and how comfortable they are with running things on the fly. The book is made for this no-prep, improv-heavy style. If that’s not your thing, you can also use the Fiction Pillars prep method I laid out to create some scaffolding to build a story around. It’s somewhat similar to Jason Cordova’s 7-3-1 method where you lay out a limited amount of pieces of fiction that might or might not be important, then give them a few details. These create solid pillars of fiction within your mind that you can always retreat towards when you come up with nothing or build around as the foundation for the session.

Reading the story kit and doing Fiction Pillars should take 30-45 minutes, and very much feels like a “prep is play” exercise as well. You’re not writing out stat blocks, you’re imagining chunks of fiction. It’s a creative exercise.

You include hundreds of magical items and potions at the end of the book in the full version. Why not also a bunch of example spells and challenges?

Oddly, I find actual items and potions to be quite a bit harder to make up on the fly than spells and challenges. I think spells, especially, are easy as we covered earlier - and they are up to the player to create. That one player usually has one job: make a cool spellcaster. That’s their whole character concept. And after they do that a few times, it gets even easier.

Magic items were the only thing I really ever saw people having trouble coming up with. That’s why they’re there. I was asked several times for more structure for them and while I didn’t want to write a set of rules, making a bunch of items with fun functions and a little piece of art was both fun to make and helpful to have in the book.

Grimwild demands a lot of GM judgment and shared player interpretation for “Messy” outcomes, backgrounds, and wises, among other things. It leaves plenty of gray area. Which kind of group do you think thrives under these open-ended rules?

You have to really enjoy momentum and flow, really stay outside of the meta channel as much as possible, and just go with the first thing that springs to mind. That kind of group can thrive in this system. If you spend a long time waffling over choices, arguing back and forth, or not accepting bad things happening in the fiction, you’re going to have a bad time. Second guessing yourself or trying to write the best possible version of the story slams up against the mechanics hard, which are trying to hurl you forward towards more scenes. You’ve got to trust your gut and the system and let that first seed of an idea win out almost always.

Okay, back to some more non-critical questions. The game is offered through a Creative Commons BY 4.0 license, opening the door to third party publishers and creators. When I was reading through the core book, I started having fantasies of seeing this game reskinned through the lens of gritty scifi, Star Wars-y scifi and Lovecraftian horror. What are some genres that you think this game would actually NOT work well with?

This is a hard one to answer. I can’t really come up with any themes I feel like Moxie can’t do, but there are a lot of themes that I can’t do. I think its limitations are more about tone than genre. It works well with anything that could be envisioned as an ensemble cast TV show, particularly those with character-driven narratives that go in emergent directions. It doesn’t like rails, and it doesn’t like too much focus on the big picture. It likes to zoom in to character moments and take its time on interesting scenes, then skip past ones that aren’t interesting.

Gameplay-wise, it doesn’t have a skill system exactly and the core resolution uses 4 stats. There’s a knowledge system (called wises) that does act like a skill system, but it doesn’t feel like the same level of simulation that you might want out of some games. It’s more permission to handwave when you need to and limitations on stuff you don’t know how to do. It doesn’t deal well with fine levels of detailed skill differences between PCs.

But I think we said the same things about most open systems before the hacking community got their hands on it. We’ll have to see what walls people hit—I don’t really want to start defining walls that might or might not actually exist.

What other books, supplements or products are currently available or will soon be available for Grimwild?

Right now, there’s the Grimwild: Exploration Deck, which is a 40-card deck that takes the exploration system from the game and randomizes it on cards, as well as including random monster entries, some fantasy-style plants, fungi, and minerals for inspiration. It has a neat way of reshuffling the deck each time and when a card is pulled that’s already been pulled, that site that you placed before then changes its dynamic.

There are two zines written by Luke Saunders of Murkdice. These are Nevermore and Gaelenvale. Gaelenvale takes place in and around a small village and feels very much like a new player tutorial mode. Nevermore is a quite challenging dungeon with an interesting isometric mapping style that Luke created. The game doesn’t really need modules, since there’s very little prep, but both of these give some stories to play through that let the mechanics of Grimwild shine.

All three of these are currently out on DTRPG.

What do you want to see happen with Grimwild in the next few years? What would be the best case scenario?

I think there are a lot of interesting directions that other creators can take Grimwild in, but I’m personally finished with the game. We’ll do a hardcover reprint of it later this year, but that’s it. As for further development, I put everything I had to give in regards to heroic fantasy into it and am incredibly proud of what Per and I managed to make. And that’s enough for me. I want to move on to new challenges.

That was the entire point of designing Moxie, to have a single system that I could build many different games upon. That freedom is the whole reason I don’t work for a company, which would probably try to double-down on each game’s success. I’m less interested in squeezing every dollar out of the games I make than I am about bringing new games into the hobby.

Here's a list of the games in the series that we’ll be working on over the next 3 years.

The Wild Frontier of Venture (weird west)

The Wartorn Lands of Prosperity (dieselpunk mech and WWI trench warfare)

The Burning Skies of Ember (Crimson Skies-inspired piloting and sky islands)

The Grand Cities of Reverie (intrigue and piracy on an oceanic world dotted with island-cities)

The Nobles Houses of Serenity (Wuxia / elemental magic and a struggle to establish a new societal order)

The Lost Colonies of Solace (Frostpunk-inspired settlement building and survival)

Grimwild links:

Grimwild Free Version (DrivethruRPG)

Grimwild Full Version (DrivethruRPG)

My Quick Look video on Grimwild

Multiple times in the last few days I'm seeing Grimwild. I picked it up and am enjoying reading it so far. Narrative play with some minor crunch around the narrative. It is hitting a good spot that I've previously not seen outside of PbtA/Dungeon World circles.

I have loved Trophy for a long time and this has some great DNA in it from Trophy and a few other great games.

Thanks for spotlighting this one. I think it could make some waves! Il br reading and writing a review before too long.