Call of Cthulhu in Japan?

I got to talk with David Trotti, the author of Japan: Empire of Shadows, a comprehensively researched megatome of a supplement for CoC set in 1930s Japan. He answered some burning questions.

Note: You can get Trotti’s seminal Call of Cthulhu supplement set in 1920s-30s Japan, Japan: Empire of Shadows, from DrivethruRPG in PDF and print-on-demand (affiliate).

Introduction

1. Hi David, can you introduce yourself and tell us how and where your life intersects with tabletop roleplaying games?

My name is David Trotti and I’m the author of Japan – Empire of Shadows, a Call of Cthulhu sourcebook for role playing Cosmic Horror in 1920s Imperial Japan. I live in Los Angeles, California, and my “day job” is as a First Assistant Director in the television industry. An Assistant Director is like a foreman on a job site. I manage logistics, scheduling and keeping people from being run over by large pieces of equipment on set. I’ve worked on shows like Star Trek: The Next Generation, Voyager and Enterprise as well as the NBC spy comedy Chuck and most recently 9-1-1 for ABC.

I began playing RPGs back in the mid-eighties in high school. AD&D and Traveller were my group’s go-to RPGs, though we tended to mix it up a lot with board games like Star Fleet Battles, Squad Leader and Axis & Allies. I didn’t begin playing Call of Cthulhu till the early 2000s, but it quickly became one of my favorite RPGs. I’ve enjoyed the move to 7th Edition and I like what Chaosium is doing with the game.

One of my other hobbies is collecting roleplaying games from Japan. During the early days of Covid, the TV industry shut down, and I found myself with time on my hands. I thought it was a perfect opportunity to translate some of my favorite material from the eighties and nineties. I started by translating the original Record of Lodoss War Replay and then moved on to things like the Neon Genesis Evangelion Roleplaying Game.

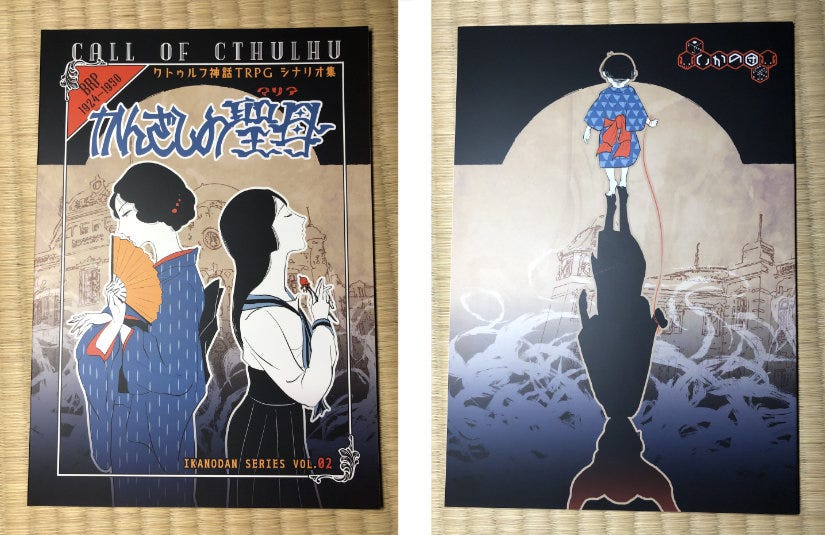

At the same time, I found myself reading a lot of contemporary Japanese TRPG scenarios. Many of them were for the Call of Cthulhu game, which was the most popular TRPG in Japan. As I was going through them, I was surprised to discover that Chaosium had never put out a Call of Cthulhu sourcebook for Japan set in the 1920s. I still had time on my hands and decided to start working on one.

Throughout Covid, I and my gaming group continued to play, though socially distanced via Zoom. Short scenarios and one-shots worked best for us, which is why I think Call of Cthulhu continues to be a staple for us.

Record of Lodoss War

2. Oh wow, first of all, thank you for your work on what I consider to be Golden Age Star Trek. That requires a whole separate interview! I do intend for this interview to be mostly about Japan: Empire of Shadows, but I first want to address your translating. I first discovered Japan: Empire of Shadows by happenstance when you posted a translation of the first couple of volumes of the original Record of Lodoss War (ロードス島戦記) playthroughs from 1988, originally published in the magazine Comtiq and later adopted into manga and multiple anime series. I have a number of burning questions here. First, how did you come about learning the Japanese language to the point of being able to translate? (I studied in Japan in college and gave the language several years of my life but the kanji ultimately defeated me).

In the sixties my father was a Marine Corps aviator stationed in Vietnam. My mother would go over to Japan to see him when he was on leave and I came within a few months of being born there. When I was young we would have Japanese students stay with us who would give generously of their afternoons to work with me on conversation, and coupled with lessons at a Japanese Buddhist school I gained some small skill, which I promptly let go fallow in my middle school years. Enough stuck, though, that I picked up a basic understanding again in High School and college. Fortunately, in Orange County, California we had a UHF channel, channel 18 KSCI, that played NHK news and programming, so I could follow along.

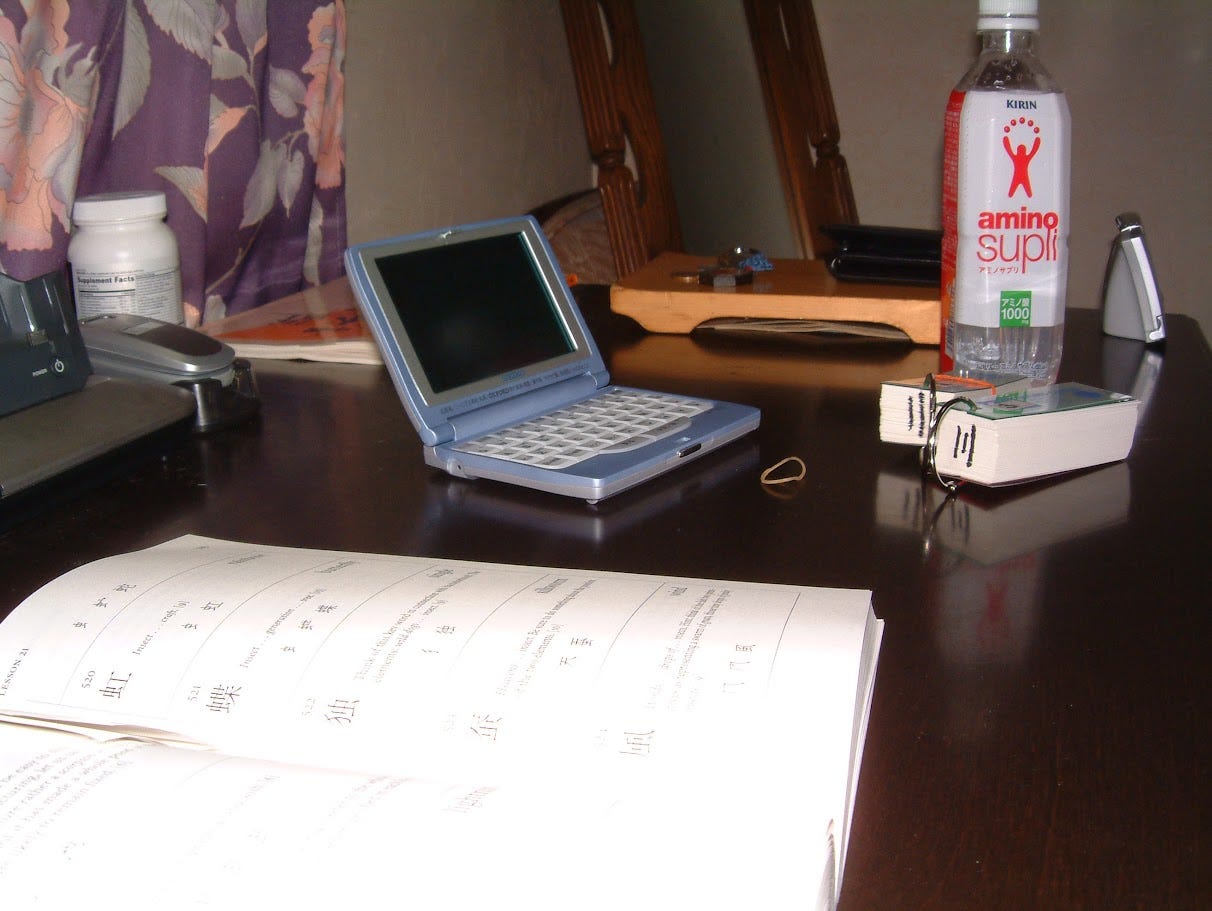

Up until very recently, I had to have my battered Japanese – English dictionary open and ready to go whenever I wanted to read something, because there are many kanji* I don’t know (and probably never will), but I’m pretty quick on pattern recognition so I’ve actually come to love radicals. My dictionary has been replaced by software, where with a few keystrokes I get the hiragana for the kanji so I can read the ones I don’t recognize, but so much of it is context, that I still often wind up going and researching the kanji anyway. Thankfully a lot of books have furigana superscripts to help with pronunciation, especially with proper names.

*(Side note: written Japanese consists of three separate writing systems: kanji, hiragana and katakana. Kanji are based on Chinese characters adopted by the Japanese in the 6th Century CE. There are around 50,000 kanji, though only 3,000 are commonly used. Kanji are composed of radicals. Knowing these base radicals, you can have a good guess at the meaning of the kanji. For example, yuki, 雪 the kanji for “snow” combines the radicals for rain 雨 and hand ヨ. Snow is a type of rain that can be held in the hand. Hiragana and katakana are parallel “syllabaries.” A syllabary differs from an alphabet in that each character stands for a complete syllable rather than just a consonant or a vowel. So in addition to a, e, i, o and u, you also have a character for every consonant/vowel combination (pa, pe, pi, po, pu, etc). And by “parallel” I mean that both hiragana and katakana stand for the exact same sounds and serve the exact same purpose, but hiragana are used to write Japanese words and katakana are used to write foreign words. Written Japanese is hard, even for native Japanese speakers, which is why many books have little hiragana letters in superscript above uncommon kanji as pronunciation guides. These notations are called furigana).

Before the Record of Lodoss War replays, I had translated a few things here and there, but mostly I was watching anime and reading gaming magazines. In 2021, a friend came across a full set of the original Record of Lodoss War replays in Japan and I thought that would be something English speaking fans of Lodoss and D&D would be interested in, so I decided to translate it. I had already read the three Sneaker Bunko books of the Lodoss replays, but I was very disappointed because the first two were not the original replays. To avoid possible legal entanglements with TSR, Hitoshi Yasuda and Ryo Mizuno and Group SNE replayed the first two stories using their own rules and new players for the Sneaker Bunko series. I was a big D&D fan and really enjoyed the Record of Lodoss War OVA (Original Video Animation) when it came out, so I was very excited to get to read the original replays which used the BECMI D&D rules. It was a lot of nostalgic fun translating them and I’ve been glad to have been able to share them with other fans.

During Covid, I had a lot time on my hands. So, I translated five Neon Genesis Evangelion Roleplaying Game books (all available on the Internet Archive). Last year, Hubz (Gaming Alexandria) added all the Comptiq magazines that had Lodoss replays in them, so I was able to translate the second replay series. I hope to get to the others eventually. Those are available on the Internet Archive as well.

I’ve been a big fan of the Japanese Call of Cthulhu scene and part of the genesis of writing Japan – Empire of Shadows came out of reading so many great and unique scenarios that Japanese authors have been putting out. Michael Reid, who wrote the excellent CoC 1920s Japanese scenario, “A Chill in Abashiri”, turned me on to a website called Booth, which is chock full of amazing Japanese scenarios. I’d love to see Chaosium and Kadokawa (the Japanese publisher of The New Cthulhu Mythos TRPG (which is what 7th Edition is called in Japan) work together to make some of that awesome Japanese material available internationally. Michael had a great suggestion in an email he sent me recently, that they should license and translate Cthulhu 2020 and Bibliothek 13 and do a massive Modern Japan book. I think that would be amazing.

I have heard rumors that Chaosium may be working on a 1980s Japan Cthulhu setting. If those rumors are true, I am totally in!

3. Thank you for validating my struggles with kanji. It really does seem like a non-native speaker needs to take monumental steps to fully learn the language! What are your favorite aspects of Record of Lodoss War as a written playthrough?

I’ll divide my thoughts based on the different replays, because there really is a significant shift that happens as they proceed.

The first replay, Record of Lodoss War 1, is what most people will immediately recognize as the source material for the animated series. It follows the adventures of Parn, Deedlit and company as they grow from first level characters to heroes, fighting evil on the island of Lodoss. It ran from September of 1986 to April of 1987 in Comptiq magazine. What I like about the original replay, is it really captures the innocent enthusiasm for gaming I think a lot of us remember from the early days of D&D. It’s rough and unpolished, and though curated to skip to the most interesting parts, you still get the sense that you’re hearing the real voices of the players and DM coming through. I also think it does a pretty good job of explaining the rules and showing how the players and DM interact to tell a story and have fun together.

The backstory on how the first replay came about is interesting. Hitoshi Yasuda, a young writer and computer game enthusiast who’d written a few articles on RPGs, was approached by Comptiq magazine to do a series of articles on Dungeons & Dragons to mark the first anniversary of the release of the game in Japan. Comptiq was mostly focused on Computer games, but the editors knew its readers were also interested in RPGs. Yasuda decided the best format for explaining how to play an RPG would be recording the actual play experience, with sidebar explanations of the core concepts, rules and observations. Yasuda asked Ryo Mizuno, who was part of the gaming and computer enthusiast group, Group SNE, to come up with a setting and serve as the DM.

Mizuno was an aspiring writer and had already been toying with the idea of an epic fantasy setting. He’d run several D&D sessions as a DM for other members of Group SNE and members using fan translations of D&D and even AD&D, so although BECMI was the only officially released version of D&D in Japan, AD&D had already crept into the house rules they were playing under. Yasuda and Mizuno gathered five other players from Group SNE to showcase the game. The setting was an accursed island full of monsters, magic and adventure. Thus was born “Record of Lodoss War.”

I don’t think anyone was expecting the response the articles received. The replay was a huge hit, so much so that even before it completed its initial run, Mizuno was already preparing a novelized version and Comptiq was hot on Yasuda to do a sequel to the replay. They also gave him his own monthly two-page column in the magazine. The art by Yutaka Izubuchi was also highly influential on Japanese fantasy. Izubuchi may not have introduced the world to long-eared elves, but he certainly took them to a new level. He also went on to serve as the art director on the Record of Lodoss War animated series.

Overall, I think Record of Lodoss War I captures the enthusiasm and raw energy of gaming that most gamers aspire to. I think Remial, a user on RPG Pub, summed it up best: “Record of Lodoss War is the D&D campaign you WANT to be in. Slayers is what you are LUCKY to be in. Knights of the Dinner Table is what you end up being in.” I love all three of those titles, but I agree, the original Record of Lodoss War game was the game I would have wanted to be in.

The second replay, Record of Lodoss War 2, picks up the story with a new set of heroes five years after the events of Record of Lodoss War I. The new party is led by Orson, a fighter with berserker qualities, and Shiris, a tough female fighter. The second series continues to use the BECMI rules, but sadly it loses a lot of the raw, improvisational energy of the first replay. I think it’s fair to call it the shinkansen (bullet train) of “railroad” plots. For fans of the Record of Lodoss War series, it’s a treasure trove of lore and world building. You get to find out what happened to your favorite Lodoss characters like Parn and Deedlit, and discover a whole other part of Lodoss island, but you really get the feeling that the world-building and planning for the novelization overwhelmed the spontaneity of the game and the players. The NPCs do most of the fighting and problem solving and the players grumble more than once that they’re just along for the ride.

I think the best lessons a DM can take away from Record of Lodoss War II are what not to do as a DM. Mizuno used the game to write his second novel, not let the players have the freedom to explore the world. The NPCs were more active than the characters, and repeatedly took charge of the game, depriving the players of actually fighting their own battles and coming up with solutions. I don’t think the second replay would have been a fun game to play in, but as a Lodoss fan, it’s a great resource for lore.

One of my favorite things overall is to hear the banter between the players. It really reminded me of being at a table with friends, slinging dice and being able to rib each other over bad die rolls and boneheaded moves.

4. Regarding Call of Cthulhu in Japan, most people I talk to are endlessly fascinated with the phenomenon and eternally hungry for more information about it. I guess my main questions about it are: Why do Japanese gravitate towards CoC more than D&D there? Are there differences in how Japanese gamers approach the game compared to English-speaking gamers in your experience? And, how much of a hand does Chaosium have in marketing and CoC content there?

I think there are several reasons why Call of Cthulhu appeals to Japanese gamers over D&D, and each reason carries its own weight for different gamers.

One big advantage Call of Cthulhu has is it uses a simple game engine (Chaosium’s BRP). It’s easy to use and doesn’t require a lot of calculations or time investment. Even better, you don’t need multiple expensive rulebooks and those rules don’t keep changing, requiring you to buy even more expensive books with each new edition like D&D.

CoC, is also about deductive reasoning and mystery solving. That makes it very attractive to players who enjoy solving a mystery over simply hitting monsters over the head for their treasure. I think that’s a big appeal to female gamers who enjoy procedural structures and mystery stories.

There’s also a social aspect to CoC that D&D just can’t match. Roleplaying in D&D often falls into tropes based on Class, Race and Alignment, whereas CoC is pretty grounded, allowing players to experiment with personas in a modern, “real world” setting. Players can push boundaries and test social limits in a safe space, while hiding behind a mask of plausible deniability provided by the character. Though it can be argued that D&D also allows for immersive roleplaying, I think a grounded setting like CoC is more conducive to actual transubstantiative roleplaying.

CoC also has the advantage of being perfect for speech-to-text and animation software making it possible for those avid Keepers and Players to hide behind virtual avatars and post their sessions online for others to watch. This creates a voyeuristic loop where the curious masses tune in to see how the players interact on a personal level, and the players and keepers get the vicarious thrill of being viewed without the risk of being recognized.

One of the interesting things about Japanese gamers is how private most of them are. I can name a handful who have actually shared their real names with me, even after working on translation projects together. Most go only by their screen names, and most of those have multiple online identities to shield their primary identity. I think there is a real hunger among many of them to express aspects of their identities that they feel they can’t express in their real lives. And CoC gives them a chance to do that.

There’s also the thrill of horror and the danger of confronting unknowable, cosmic evil. Even though it is just a game, it’s like a good horror movie. The risks the characters take and the jump scares Keepers provide are thrilling. It’s like being part of a ghost story, where you can interact and shape the story while trying to solve the mystery.

As for differences, I’ve noticed that most Japanese CoC scenarios tend to be modern, whereas most western CoC scenarios tend to be set in romanticized historical periods (like the 1920s or Regency era). Western scenarios focus on accomplishing missions, whereas Japanese scenarios tend to favor saving a particular NPC or group of NPCs. Japanese scenarios tend to have a lot more pre-written expositive text the Keeper has the option of reading aloud, where western descriptive text tends to be more general, requiring the Keeper to provide the tone and color. I’ve also noticed that there’s a lot more humor in Japanese CoC sessions. Though certainly not universal, there’s often a broadness to the characters and their reactions to unspeakable horrors that edge into comedy. Whether this is a “stress release” device or influenced by anime which tends to play such things broad, I can’t put my finger on, though it could be a bit of a “chicken or the egg” question. Perhaps the broad comedic strokes in anime and RPGs that leave us scratching our heads in the west is a “stress release” safety valve that Japanese audiences prefer.

I can’t really answer how much of a hand Chaosium has in marketing and content in Japan. Certainly, through Kadokawa, they have an excellent brand presence and great market penetration. But the official releases are dwarfed by the fan content, so I think there’s a great hunger for official content. Personally, I think that’s a good thing, because successful fan material means eager fans, which means more people who want to buy core books when they do come out. Japan is a very special market where it’s hard for outside entities to gain traction, so I think Chaosium is doing the right thing by allowing the fans to make the game their own.

Japan Empire of Shadows

5. Thank you, I am now enlightened on the subject of Call of Cthulhu in Japan. And on that note, please describe Japan - Empire of Shadows for us.

As you can tell, once I get started on a subject, I tend to get excited and keep going on and on. Which is sort of how Japan – Empire of Shadows grew into the hefty 400 page beast that it is.

What is Japan – Empire of Shadows?

The elevator-pitch would go something like this: “Japan - Empire of Shadows is a Call of Cthulhu sourcebook for roleplaying cosmic horror in 1920s Imperial Japan. The 400 page book includes 334 unique locations, 35 full color maps, over 70 NPCs, 20 player handouts, six pre-generated characters, new spells, new Mythos tomes, new monsters, a concise history of the land, people and nation of Japan and much more. It is available as a PDF and Print-on-Demand on the Miskatonic Repository on DriveThruRPG.”

Why write a sourcebook on 1920s Imperial Japan?

When I set out to write a guide for hunting the Mythos in 1920s Japan, I didn’t plan on it being 400 pages, and I certainly didn’t expect it to be a comprehensive sourcebook. I just wanted to provide a useful list of locations, NPCs and story hooks for Keepers looking to take their investigators to Japan. I also wanted to offer some suggestions for roleplaying the culture-shock foreign investigators might experience pursuing supernatural creatures in Japan. I was inspired by Chaosium’s Community Content program, the Miskatonic Repository, which allows Community Content Creators to release their own Call of Cthulhu related material on DriveThruRPG.

With the popularity of anime internationally and all of the amazing Japanese CoC content out there, I was surprised that Chaosium hadn’t developed a 1920s sourcebook for this amazingly rich setting and I didn’t see one on the horizon. I like Cthulhu. I like Japan. So it struck me that if I wanted a 1920s Call of Cthulhu sourcebook for Japan, I was going to have to knuckle down and write one myself.

On the process of writing the book.

I started outlining in December of 2021. My inspiration was the old Secrets of Los Angeles sourcebook. I really love the way it’s laid out, with good maps that give the reader a sense of where the locations are, who the investigators could run into at those locations and some great story hooks. It’s one of my favorite sourcebooks and I think anyone who compares the two will see the seeds of J-EoS in SoLA.

I was also inspired by Enterbrain’s Cthulhu & Empire, a third-party Japanese sourcebook for CoC set in Taisho Era (1920s) Japan. Enterbrain, along with Cthulhu’s major publisher Kadokawa, are licensees of the New Cthulhu Mythos TRPG in Japan. ( For reference, 7th Edition Call of Cthulhu is called the New Cthulhu Mythos TTRPG (新クトゥルフ神話TRPG) in Japan rather than the “Call of Cthulhu RPG” (クトゥルフの呼び声RPG) . (Side note: I think this is a better title for the game, because it expresses that the game covers a broader scope of Lovecraft’s canon than just one book.)

Anyway, I enjoyed reading Cthulhu & Empire, but it’s not a very useful sourcebook for international Keepers and players. First, it’s in Japanese, but more importantly it doesn’t have any maps linked to locations to provide context, it doesn’t have any specific locations for Keepers to use as examples and it doesn’t have a good selection of NPCs for gaming use. It also doesn’t really explain a lot of things international Keepers and players would need to know about 1920s Japan, because it takes for granted its audience already is aware of the unspoken complexities of Japanese society. What it does have, though, are three great scenarios in the back that are awesome and I hope someday Chaosium and Kadokawa work a deal to release them internationally. (For those curious, the three scenarios are "Asakusa Ryounkaku," "Ginza Spiral" and "Spirit Amber of Ponape.” “Spirit Amber of Ponape” still haunts me to this day.)

So, with the structure of “Secrets of Los Angeles” in mind, I began outlining a 120-page sourcebook. My goal was to do 40 pages of “local color,” 40 pages of “locations and NPCs” and 40 pages of “scenarios/spells/Mythos creatures.”

Very quickly the scope of the project began to expand. As I researched and mapped out potential locations, NPCs and story hooks, I went down the rabbit hole of the rich tapestry of 1920s Japanese life and culture. I also discovered how intertwined the spiritual world of Japan in the 1920s was with daily life. Many Japanese ghost stories and legends are grounded in actual locations, locations that can still be visited and explored.

Originally, the sourcebook was just going to cover Tokyo, but as I continued researching material from the National Diet Library and at the public library here in Los Angeles, I ran across old guidebooks for Japan from the 1920s with awesome woodblock print maps of several other major cities. At that point, I figured if there was ever only going to be one sourcebook for 1920s Japan, this was going to be the definitive sourcebook any Keeper could ever want. I debated doing it as three separate books (Tokyo, Cities of Japan and Cities of the Empire), but I realized most people would prefer having it all in one volume.

6. I feel like I’ve climbed into a time machine when reading this book. It reminds me of one of my favorite books, The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England by Ian Mortimer. The main characteristic is that it acts like a travel guide and gazetteer, jumping from topic to topic in order to give an overall feel of a world. Can you go more into the structure and content of the book?

I like that analogy and now I’m going to have to seek out Mortimer’s book. You’re right, I did want to emulate the feeling of a period travel guide. There was even a version of the book where I included “handwritten” annotations in the margins, as if this had once been the personal travel guide of a Miskatonic University professor. A few vestiges of that still remain among the handouts where there are vague references to a Miskatonic University investigation into the meteorite from the “Color Out of Space.”

Above all, I wanted the book to be entertaining and educational and what appealed to me in the travel guide format was it was an opportunity to present real places, people and events set in a fictionalized Lovecraftian universe. I think people like to feel they’ve come away from a book having learned something on a subject, while still having fun. If, after reading Japan - Empire of Shadows, a reader feels they have a better understanding of Japan, geographically, culturally and historically and meanwhile they enjoyed Easter-egg hunting for the Mythos references along the way, I think that’s a win.

That’s also why maps are very important to me, and not just modern or fictionalized maps, but period accurate maps. I’m a very visual learner and maps give me context. They allow me to understand how things fit together: how people move from place to place; how locations tie together; how physical spaces shape different ways of seeing the world. There are a lot of maps in the book. They serve as concrete references that the reader can always turn back to for context or as a visual aid. Just as street maps in a normal travel guide can keep a traveler from getting lost in a new city, the maps in Empire of Shadows are designed to help the modern reader from getting lost in the unfamiliar setting of 1920s Japan.

As for structure, the book has eight chapters and six appendices. Chapter 1 covers Japanese life, society, history and culture, with an emphasis on how that affects gameplay. Chapter 2 outlines the three Narrative Threads (more on those in a moment). Chapter 3 is all about the City of Tokyo, with maps, locations, NPCs and story hooks set in the Imperial Capital. Chapter 4 covers eight other cities in Japan, including Kyoto, Nagasaki and Osaka. Chapter 5 expands the action to territories either occupied by Japan at the time or important to the Japanese empire, like Korea, Taiwan and the South Seas Mandate, which includes the mysterious island of Ponape and the Nan Madol ruins. Chapter 6 is about various Citizens of the Empire, divided by the Good, the Bad and the Gaijin for Keepers to use or draw inspiration from in creating NPCs. Chapter 7 is a deeper dive into Japanese history, society, military, police, medical and mental health systems for Keepers who want to get really immersive. Chapter 8 covers the myths and Mythos of Japan, offering Japanese inspired takes on classic Mythos creatures, along with creatures, tomes and spells unique to Japan.

The six Appendices cover goods, weapons, vehicles, travel options, new skills, inspirational media, player handouts and six pregenerated characters useful for both players and Keepers planning adventures in Japan.

The three Narrative Threads are actually three campaign-sized scenarios that span the breadth of the empire. “Upon A Stone Altar” takes the investigators into the Japanese controlled South Seas, to islands like Okinawa and mysterious Ponape, home to the Nan Madol ruins. “Color from the West” takes the investigators into occupied Korea in pursuit of mysterious glowing coal that is sucking the life out of people and unleashing unspeakable horrors. “Kamuy of the Northern Sky” moves the action north into the forests of Hokkaido in search of an ancient pyramid that predates human history.

The reason I call them as Narrative Threads, is because rather than putting them in the back of the sourcebook as separate scenarios, the entries for each thread are woven throughout the book, making the information for the story available at the location where it takes place. For ease of reference, the entries are color-coded and Chapter 2 contains “Thread Maps” showing where all the entries occur, along with the traditional synopses, NPC descriptions and story arcs for each thread. I went with this structure, because of my own personal frustration as a Keeper with always having to keep turning to the back of the book for scenario information, then hunting through the sourcebook itself to find the locations where they take place. This way, the story beats, NPCs and monsters are all where they take place, along with the location descriptions, maps, pictures and easy access to the adjacent locations the investigators are likely to visit.

7. How and where did you develop all of the information, maps and beautiful imagery for this book?

Most of my research was done scouring Japan’s National Diet Library and the American Library of Congress. The research took a long time. I started by breaking Tokyo up into eight sections and creating a map for each of those sections. I wanted between 10 and 20 locations on each map. Then I did the same for each of the cities in the other chapters. I would have loved to have done one big fold-out sheet map for Tokyo, but I knew I was limited to 8.5X11 pages, so the smaller maps seemed the most versatile.

I determined the locations I wanted to include by consulting period guide books, historical records and researching supernatural stories. Most of the locations fell into place naturally and many were easy to document, thanks to a keen interest in photography among the Japanese in the 1920s and many excellent period guide books catering to both Japanese and English-speaking tourists.

The Tokyo maps were largely based on a 1918 Tokyo City map. I supplemented it with US Air Force survey maps from the 1940s, a 1945 occupation map and period aerial recon photos for accuracy. I used Google Maps and satellite views to confirm present-day locations and occasionally tweaked roads for accuracy.

Luckily, Japan in the 1920s was experiencing an explosion of artistic expression, and there is a plethora of wonderful art depicting all aspects of life, including landscape and architectural subjects, which I drew heavily on for illustrating the location descriptions. I wanted to capture as much of the breadth of Japanese art from the period, so the images used represent not just traditional styles like Ukiyo-e wood block printing, but also emerging styles like Shin Hanga (with its manga-like color illustrations), western styles like oil on canvas and especially photography.

I was also blessed by the fact that the Japanese are avid enthusiasts on any subject they put their mind to, and this includes the archiving of architectural plans and even the preservation of entire buildings in dedicated architectural parks. Many of the floorplans presented in the book are of the actual buildings and some of those buildings can still be visited at places like the Meiji Mura park.

The layout of the Imperial Palace required a lot of piecing together. I used Meiji era construction plans, an aerial photo from the 1920s and the 1945 US Occupation site plan. Much of the Daikancho and Imperial Guard HQ had to be mapped based on period woodcuts and even Edo era references. The location of the Matsu no Oroka (Pine Corridor) is known historically, but it no longer exists except in legend. During the 1920s, security at the Palace was very tight and accurate maps were considered state secrets. Most of the palace and the architectural designs were destroyed in the 1944 fire bombings of Tokyo, so outside of academia, Japan – Empire of Shadows probably has the most complete description of the Imperial Palace from the 1920s in existence.

Most of the other cities were based on period tourist guide book maps, both in English and Japanese. Ponape Island is based on a German survey from before WWI (circa 1915) and the Nan Madol ruins are based on modern archeological maps and satellite views. The location of the pyramid mountain in Hokkaido is based on a satellite view and triangulated from the Chashi fort near the Kamui-Kotan train station.

Things I am proudest to have tracked down include the Kiringul in Heijo (a legendary Kirin’s lair outside Pyongyang, Korea), Kinokunizaka Slope in Tokyo (site of the legendary tale of a faceless ghost) and the Shochiku Kamata Film Studio (where many classic silent films were shot).

The maps are as historically accurate as research and modern satellite mapping can make them.

Along the way I abandoned a lot of superfluous but fun rabbit-hole stuff. For example, Japan's key geomantic ley-line really does line up with a lot of supernatural locations across Japan. And early Japanese jindai moji (a writing from the legendary age of the gods) and classical Mayan bear an uncanny resemblance, but I didn’t have the expertise to do that deep of a dive into the possible connections between ancient Japan and the ancient Maya. I also got sidetracked by Sakai Katsutoki's Pyramids of Ancient Japan book and felt compelled to translate it.

I originally had five scenarios, but I cut down to the three narrative threads because the book was getting too big. The other two scenarios were set in Tokyo and were designed to introduce investigators to the city. I went with the three sweeping narrative threads because they covered the empire from end to end (each going a different direction) and I wanted to give Keepers the tools to create larger campaigns.

The narrative threads were largely composed at the same time that I was laying out locations in the book. I knew I wanted to explore Japanese occupied Nan Madol and the lost continent of Mu. I had read Katsutoki Sakai's book Pyramids of Ancient Japan and hunting for an ancient Japanese pyramid in a remote part of Japan seemed pretty awesome. The Color from the West thread, set in occupied Korea, originally continued up into Harbin in Manchuria, but it got too cumbersome and so I broke off the Harbin portion and made it its own bit with the plague angle.

The "story hooks," like the vengeful fox spirit, developed largely on the fly as I came to new locations and wondered what kind of horrors could exist there. I also had some story hooks in mind before writing and plugged them in when I found a good place for them (like the plundered fortress mound near Hakodate).

8. For anyone unfamiliar with early 20th century Japanese history, it was a moment where the country emerged from a sort of hermit island into a rather brutal but short-lived imperial terror in Asia. So you had to handle that aspect with some care. How did you find the right tone, theme and cultural sensitivity?

One of the hardest parts of writing the book was finding the right tone. Japan in the 1920s was a vibrant and intriguing setting, but it was also a highly controversial time. As an outsider, I felt a special responsibility to portray it properly. I approached it with the following five principles at the forefront of my mind: I did not want to perpetuate negative stereotypes. I did not want to come across as an "apologist" by painting an idealized portrait of Japan in the 1920s. I did not want to demonize 1920s Japan unfairly either. I wanted to keep the Mythos separate from real human evil. I wanted to make the environment fun and playable as a game setting.

In approaching the portrayal of the period (and then relating that to the development of a connective "theme" that runs through the work, extending to the story hooks and characters), it took several passes to finally land the tone I was after. As a general theme, I felt repression and rebellion were natural subjects to explore within the Japanese Empire at the time. Whether it is through Korean students fighting for their country, a fox spirit seeking revenge against exploitive oligarchs, a female PC standing up to blatant sexism or a young Ainu woman trying to do what she can to preserve her people's past from cultural genocide, those were explicit choices, but I think the line blurs in the creative process between a deliberate choice and a natural expression. At a certain point, the character tells the writer who they are much more forcefully than the writer can force a character to be something it isn't.

I also had to rein myself in quite a bit. The book is advertised as a game sourcebook, not a college textbook, so I could not dive into subjects nearly as deeply as I wanted (such as having a deeper discussion on Zen and the Japanese people or exploring the history of the Japanese writing system). I did push the boundaries on some topics, though. I had been warned that I might get into trouble (and the book might get pulled from the Miskatonic Repository) if I portrayed members of the Imperial Family as NPCs, hinted that the Japanese might be descendants of the survivors of some mythical lost continent called Mu (even in a wholly fictional manner), or suggested that Taiwan might not always and forever have been part of mother China. Needless to say, I ignored these calls to censorship. The Imperial Family make cameos as NPCs. Lost Mu is hinted at in all its 1920s pulp glory. And China’s claims to Taiwan are solidly refuted as being based on modern China’s colonial imperialist ambitions, not actual historical, legal or moral standing.

You pointed out a very interesting aspect of Japan’s rise from isolated island nation to aggressive regional power in the lead-in to your question and I think it deserves some small treatment here. As you noted, Japan went from being a backwater, isolated, agrarian island nation to an international industrial powerhouse in less than 70 years from 1850 to 1920. At the same time it went on an aggressive campaign of expansion at the expense of its neighbors, ultimately resulting in its defeat in the Second World War. It is important to note that none of these things happened in a vacuum, and many factors, both internal and external, shaped how Imperial Era Japan rose and fell so swiftly. The 1920s are an interesting and pivotal moment for Japan, but sadly they are little studied and understood.

History is made by humans and to understand the history of Japan in the 1920s it is important to understand the two men who defined its Imperial Era: the Emperor Meiji (1852-1912) who ushered Japan into the modern age and his grandson, Crown Prince Hirohito (1901-1989) who oversaw its most turbulent years.

The crisis point for Japan occurred in 1853 when Commodore Perry lead an American fleet into Tokyo bay and forced Japan to open its ports. Prior to that, for 250 years, Japan had maintained its isolation from the outside world. This is not to say that the Japanese were unaware of events beyond their shores. If anything they were extremely distressed by Europeans carving up China, Siberia and the Indo-Pacific. But the response of the Tokugawa Shoguns had been to maintain Japan’s steadfast isolation in the face of western encroachment, trusting to its island status to defend it. The arrival of the modern world with gunboats and long-range naval cannons shook Japan to the core, because the Japanese saw the fate of their neighbors now at their very shores.

But instead of rising up, the Shogun ruling the nation from the bureaucratic capital of Edo hesitated. The Shogun accepted unfair treaties forced on the Japanese by the European powers, ceding foreign settlements in the major port cities and lopsided trade agreements. Down in western Japan, which had a long history of dealing with outside powers, the leaders of three key domains saw the imminent destruction of Japan, and sent emissaries to the sixteen-year-old Emperor Meiji in the imperial capital of Kyoto, asking him to restore the empire and overthrow the Shogun. The ensuing Boshin War lasted two years and in 1869, the now 18 year old Emperor Meiji marched into Edo at the head of his victorious army and renamed his new capital Tokyo.

But Meiji’s troubles weren’t over and the intricate web of alliances that held Japan together politically would have tragic consequences in the future. To “pay off” the southern domains for their support, the Emperor allowed them to go on expansionist campaigns abroad to enrich themselves. The Satsuma domain took the Ryukyu islands and Taiwan in the name of the empire, while Choshu set its sights on the mainland, namely Korea and Manchuria. This rivalry would play out in the deep strife between the Navy which was largely comprised of Satsuma men and the Army which for many years was dominated by the men of Choshu.

This set a precedent, however, where the Emperor would tacitly greenlight imperial expansion behind closed doors, while explicitly not taking a position on it publicly, effectively keeping his hands clean through a veil of plausible deniability. It was a tactic Meiji’s grandson Hirohito learned well.

The Japanese also took the opportunity their new open borders allowed, to learn everything they could about the rest of the world. For decades they sent scholars and students abroad to study and accumulate knowledge. These young emissaries returned with high ideals and unparalleled zeal. The young Emperor Meiji and his key advisers absorbed this knowledge and using it, forged a new path for Japan. Unfair agreements were rewritten into proper treaties by Japanese lawyers trained at Oxford and Yale. Medicine and science were imported and endorsed by doctors and scientists educated in Germany and France. But Japan also took to heart the darker lessons learned from the west as well. Japan saw that western success seemed to be linked to aggressive colonialism. The Japanese were late-comers to the table, and they were determined to make up for lost time.

The Emperor Meiji saw in Imperial Russia, the sick man of Europe, the perfect opportunity to satisfy those imperial ambitions, strike at the Europeans and bring the forces of Satsuma and Choshu together on a joint venture. Using the Navy and Army in a combined effort, the Japanese opened the 1904 Russo-Japanese war with a sneak attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, near Dairen, China. The success of this sneak attack would become a hallmark of Japanese military doctrine.

Having defeated the Russians, Japan found itself a rising global player. It joined the allies in the First World War and gained significant possessions in the Pacific from the defeated Germans. Its factories dominated trade in the post-war years as European factories struggled to recover. But it also faced many crises brought on by its own expansionist policies. The other colonial powers chafed at Japan’s unbridled expansion into Asia and the Pacific. America and Britain in particular saw in Japan’s ambitions in China and the oil-rich region off the coast of Indo-China, a future rival. Economic sanctions, immigration bans and lopsided arms reduction pacts began to isolate and embitter the Japanese. This is not to present an excuse for what the Japanese Empire later did, but to present a context to it. Japan saw itself as a victim of western colonial expansion and it saw itself as a liberator of its Asian neighbors from European domination. Sadly, it chose to replace western colonial rule with its own, even more severe, form of repression.

In the midst of this era of tumultuous change, in 1912, the Emperor Meiji died and his son, Yoshihito became the Emperor Taisho. Taisho, however, was physically frail and it is widely believed by scholars that he was mentally incompetent. The hopes of the empire therefore fell upon the young Crown Prince Hirohito, who was a boy of twelve when he found himself being called upon to handle the affairs of state for his infirm father.

Hirohito, by all accounts, made up for his father’s deficiencies with a keen mind and quiet nature. He was his grandfather’s favorite and was raised in the company of his older cousins who were dubbed his “big brothers.” Many of these “big brothers” were related to Hirohito through intricate webs of marriage arranged by the Emperor Meiji using his sisters and daughters to cement alliances, particularly among the powerful Satsuma and Fushimi clans. These youthful friendships shaped Hirohito’s worldview and drove him deeply into the camp of the Satsuma and away from the Choshu. For anyone who wonders why Japan chose to attack the United States at Pearl Harbor rather than focus on knocking Russia and China out of Siberia and Manchuria, one need look no further than the marriage records of the imperial family from 1900 to the 1930s. The seeds of the Second World War were sown in the marriage alliances to the Fushimi and Satsuma and that clan's ambitions in the Pacific, Taiwan and South East Asia using the power of the Satsuma dominated Imperial Navy.

In the 1920s, however, war with the west was far from a foregone conclusion, and Taisho Era Japan existed in a wildly colorful and inventive bubble of relative peace and freedom called the “Taisho Democracy.” It was typified by an unbridled optimism for the future, very reminiscent of that of America. Art and culture flourished, and there existed a strange collision between traditional Japanese and western cultures that resulted in fascinating hybrid of the two. I think it is a mistake to dismiss the modernization of Japan as cosmetic mimicry of western culture. The government and people of Japan in the Meiji era took decisive and self-aware steps into the modern world, bending foreign forms to suit their unique society and carving out a cultural identity that remains distinct. Certainly there were significant problems and an underlying darkness. Ethnic minorities like the Ainu and Koreans were horribly mistreated and the genocide perpetuated upon the Ainu in particular has direct parallels to the plight of native Americans in the previous century. The Empire of Japan was a repressive imperial power, occupying Taiwan, Korea and portions of Manchuria. Buddhism was heavily repressed in favor of the state religion of Shinto. Free speech was restricted and the Tokko Special Higher Police (the equivalent of Germany’s Gestapo) maintained order through fear and intimidation.

I’ll conclude my thoughts on the subject by quoting from Japan - Empire of Shadow’s Introduction:

“This book is not intended to diminish or excuse the horrors inflicted by the Empire of Japan on the peoples of Asia prior to and during the Second World War. Fictional dark gods and elder beings are no excuse for real evil in the world. But part of the power of historically informed role playing is the ability to present history in an engaging and informative manner. By encouraging Investigators to shine their lights into the darkness, Call of Cthulhu is in a unique position to reveal the manmade horrors of this world so that they are not forgotten or repeated.

No portion of this book is meant to disparage or demean the current government of Japan or its people who have striven since the end of the Pacific War to renounce military aggression, address racial and gender discrimination and promote human rights, free speech and democratic values. The sins of the former Empire of Japan portrayed in this book are not meant as criticisms of the present democratic nation of Japan, but rather an opportunity to bring a time of darkness and shadows into the healing light of a newly risen sun.”

9. What tips do you have for anyone considering writing for the Miskatonic Repository?

Start by outlining your project in a text document like Microsoft Word or even writing it out with pencil and paper. Having a clear outline is vital to organizing your thoughts. You can always change your outline as the book evolves, but writing down the plan gives you a map you can always refer back to as you move forward.

Create folders for collecting your reference material and keep a record of where you get your information. Not only will this help you later when you need to establish where things like photos and art came from, but it will also allow you to go back and cite your references properly and do additional research at sites you liked.

Writing is rewriting. And good writing is editing, editing and more editing. Have someone you trust act as your editor and proofreader. You would not believe how many typos, incomplete sentences and disconnected thoughts made it through my multiple passes and reviews. Your eyes will lie to you, seeing words you imagine you wrote, periods you know you added and ideas that made complete sense to you at the time.

Proofread and finalize your text BEFORE you put it into your layout. Trying to edit your text after laying it out is a recipe for disaster.

Use a layout program like Adobe InDesign. Do not try to do layouts in Microsoft Word (unless it’s really, really short). I did my layout in InDesign. I am not an expert in doing layouts. In fact, doing this book was my first time using InDesign. I learned how to do it from an awesome video on YouTube by Kat Clay who walks you through the process. I cannot recommend Kat’s video enough. It saved me countless hours of frustration and sanity loss.

Art should be 300DPI and the size you want it to appear on the page or slightly bigger. I wish I had known this in the beginning, because I had to go back through and change every image. And when you’re talking about a 400-page book, that was a lot of images.

Manage your expectations. Most Community Content books will only sell 50 or fewer copies. Write because you’re passionate. Write for the ages. But balance that with the knowledge it’s probably not going to make much money. Japan – Empire of Shadows was a passion project. I fully expected only to sell around 50 or so copies. It has done better than that, but even so, I would argue I haven’t broken even based on the time I spent on it. Still, I don’t regret the experience at all. I had fun. I learned things. I’ve gotten to meet and talk to people I wouldn’t have met otherwise.

The most important thing, though, is “write it down.” If you have something in your head, put it on paper. Make it concrete. It doesn’t have to be good or coherent. It just has to have physical form. Once it’s written down, it becomes real. It becomes something you can mold and shape into what you want.

Too many people fear the blank page. I know that fear. The fear of starting down a path that makes no sense, wasting time and creative energy. The truth is no time spent writing is wasted. The initial draft of Japan – Empire of Shadows was around 300,000 words. Most of the ideas were rough approximations or loose collections of ideas and notes. It took many, many passes through the manuscript to make it say what I wanted.

If you have something to say, don’t worry. The words will come. The real writing begins with the subsequent opportunities you’ll have to craft those words into cohesive, compelling thoughts.

So go and write and let yourself be surprised by where your words take you. I never imagined when I began that I was going to take a 400-page journey into 1920s Japan. I’m glad I went on that journey, and I’m grateful to those of you who’ve joined me on this uncharted ramble through my thoughts.

10. Okay, let’s say someone has read Japan Empire of Shadows and internalized all that historical knowledge. What other RPGs do you think could work with 1910s-1930s Japan?

Vampire the Masquerade by White Wolf might be a fun twist on the vampire genre. The political intrigue among warring vampire clans in Japan, set against the backdrop of the Taisho Era sounds intriguing.

Pathfinder has an interesting Asian-inspired Steampunk setting from Fat Goblin called Steampunk Musha. I think 1920s Japan and Steampunk would be an awesome collision.

To switch it up, I’d like to also mention some fun Japanese TRPGs that have been translated into English and are worth checking out.

Ryuutama is a unique TRPG that emphasizes the journey over the destination. It’s a charming, fun game that’s more about enjoying the trip than buffing for a final battle.

Shinobigami is one I’ve been meaning to try. It sounds like a blast. Short, sweet and kickass.

11. I want to share with you three little details from the period that I would have to include in my first campaign using Japan - Empire of Shadows. 1) The dilettante who funds a very obscure and dangerous expedition, but insists on being a part of the traveling group. 2) The overly eager hotel “room boy” darting in and out of the investigators’ room, causing privacy issues and great consternation, and 3) Meeting Lafcadio Hearn, the prominent English-speaking writer who settled in Japan as a professor and harbored a lifelong interest in the supernatural. What are some of the most irresistible details from the setting that you have inserted into a game session?

Those are great NPCs. I would love to run into Lafcadio Hearn. He was such an interesting person. His book, The Kaidan (Strange Tales - a collection of Japanese ghost stories) served as the inspiration for a good number of encounters in Empire of Shadows. NHK did a four-part dramatization of his life in 1984 called “Glimpses of Japan” starring George Chakiris as Hearn. Here’s a clip where Hearn’s Japanese wife tells him some of the ghost stories that would make it into The Kaidan. Glimpses of Japan Clip

The rich Japanese benefactor is a great means of getting the investigators into the story and a great device for getting them in and out of trouble as needed to propel the story along.

For me, I’d love to incorporate the Japanese mystery writer Edogawa Ranpo (the pen name of Tarō Hira; a play on the name “Edgar Allan Poe”) as an NPC for the players to come across. He was known for his macabre stories and his explorations of the darker side of Tokyo. He probably would have made an excellent investigator in his time.

Some of the setting material is drawn directly from my own sessions. The “Kamuy of the Northern Sky” scenario was one of my first attempts at setting a campaign in 1920s Japan. The NPC Katsutoki Sakai is a real person from the 1920s, who actually hunted for ancient pyramids in Japan and wrote a book on the subject (appropriately titled “Pyramids of Ancient Japan”). In Empire of Shadows, he serves to introduce the investigators to the “Kamuy of the Northern Sky” Narrative Thread, which culminates in a hunt for a pyramid in the snowy forests of northern Hokkaido. Sakai’s core theory was fascinating, but his methodology and conclusions were way out there. Sakai proposed that a prehistoric global civilization, centered in Japan, had worshiped their heavenly gods from atop the perfectly symmetrical sacred mountains of Japan. He believed that this tradition was carried around the world by that proto-civilization and that the pyramid builders of Egypt, the Middle East and Central America were trying to recreate the sacred mountains of Japan by building pyramids to worship atop.

I really felt strongly about using the island of Ponape (modern day Pohnpei), home to the mysterious Nan Madol ruins, as a gateway to the lost continent of Mu. The Nan Madol ruins were referenced by Lovecraft in his writings, and served as the model for the cyclopean city of R’lyeh and the sunken temple of Ghatanothoa. In the 1920s, Ponape was part of the Japanese South Seas Mandate, and had a Japanese agricultural station and garrison there. I remember as a teenager reading Churchward’s book on the Lost Continent of Mu. Churchward’s theories have been disproven by modern science and sea floor mapping, but since the setting is in the 1920s when lost continents could still exist, I decided to embrace it. I also really enjoyed one of the scenarios in “Cthulhu & Empire” set on Ponape, titled “Spirit Amber of Ponape.” It’s a great scenario that I hope someday gets released in English.

Ponape and Nan Madol appear in the Narrative Thread “Upon a Stone Altar” (the name “Pohnpei” translates as “Upon a Stone Altar,” which comes from a legend that the island was raised by magicians and built upon a great submerged stone altar). What also appears in that thread is a submarine, the IJN O2. The submarine O2 actually existed. It was a captured WWI German U Boat that the Japanese were in the process of converting into an underwater salvage vessel. The O2 vanished in a storm, but years later, it was sighted in the mid-Pacific off Hawaii. A boarding party from the freighter Liberty attempted to board her, but they were driven back by noxious gasses. A few days later, the US Navy sank the O2 as a “navigational hazard.” That version of the O2 and the hapless crew of the Liberator that boarded her served as its own gaming session. Empire of Shadows depicts an earlier incarnation of the submarine O2, before it vanished.

One of my favorite “real life” inspirations that I had to incorporate is the Imperial Hotel itself.

Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, the Imperial Hotel is probably one of the most iconic and improbable buildings to have ever existed in Tokyo. It was essentially a Mayan pyramid dropped down into the heart of Tokyo with all the modern amenities of a luxury hotel and the iconography of ancient Mexico. I put a large amount of research into the hotel, from recreating accurate floorplans, to tracking down extant color samples of the furniture and materials. In my own games, I tend to encourage the players to use the Imperial Hotel as a “base of operations” by making it the “Rick’s Bar” from Casablanca of 1920s Tokyo (“Everyone comes to Ricks…”). It’s stocked with interesting and useful NPCs, has a built in mystery (“Why is it built like a Mayan pyramid?”) and has clean sheets, private baths, room service, car rentals and a Japan Tourist Bureau office.

12. Can you list some scenario recommendations for Keepers looking to take their investigators to 1920s Japan?

The Bride of the Goat Available on the Miskatonic Repository. Written by the Japanese author, EDO-RAM. Bride of the Goat sinks its teeth into its “remote mountain village” location and never lets go as it drags the investigators deeper into the ancient mystery beneath a quaint local ceremonial custom. A good scenario for moderate level investigators.

Makami Sakura Available on the Miskatonic Repository. Written by the Japanese author Momiji Kuzunoha. Makami Sakura (“Cherry Tree of the Wolf God”) is a great scenario for introducing players to Japan in the 1920s. The setting is rich and colorful, the hook straightforward and the mystery is compelling.

A Chill in Abashiri This is Michael Reid’s awesome CoC scenario set on the northern island of Hokkaido, in Abashiri Prison. Well laid out with some great hooks. The mid point will surprise the players and leave them desperate to escape a prison that no one was ever meant to escape.

Cream Soda Cream Soda is one of my favorite scenarios of all time. Presently it is only available in Japanese. I’ve worked with the author on a translated version and am hoping they’ll put it up on the Miskatonic Repository. Even though the link goes to the Japanese language version, the author has decided to make it free, so for anyone interested in Japanese CoC scenarios on Booth this is an amazing opportunity to try one out for free and see what Booth is all about.

Teito Monogatari This is EDO-RAM’s Taisho Era Call of Cthulhu website. It is a boundless well of Taisho Era knowledge and has a large selection of free scenarios he’s written. It’s in Japanese, but most web browsers have translation functions so, please, check it out.

13. If you had the time and motivation, what would be an area of this historical setting where you could write an expansion book for Japan - Empire of Shadows?

At the moment, I’m working on a translation of the campaign 帝都大混沌遊戯 ("Imperial City Great Chaos Game") along with a fellow CoC player, Yumiko Ishigaki. The campaign is a 132-page collection of five connected scenarios by five Japanese authors. It’s set between 1920 and early 1923, before the Great Kanto Earthquake, and explores different parts of Tokyo in different seasons. It came out last year on Booth. Yumi and I are going back and forth with the authors for clarifications and to make sure they’re happy with the translation. If all goes well, we’re hoping the authors will put it up on the Miskatonic Repository this Summer (2024).

I’ve also been outlining a solo scenario as a companion piece to Empire of Shadows, but haven’t had much time to devote to it just yet. It takes one of the scenario hooks from Empire of Shadows and expands it into a full-fledged investigation into dark happenings in Tokyo and leads down to Ise Bay, centering around the disappearance of several Ama (female pearl divers). I thought it would be fun to present something that a Keeper (or players) could explore on their own, getting a feel for some of the unique aspects of 1920s Japan in preparation for a group session. I’d like to do it as an homage to Edogawa Ranpo by making it a really twisted mystery to solve.

I think a good companion sourcebook would be one that focuses on rural settings, small villages, dark forests and lonely shrines. Empire of Shadows focuses on major cities, because places like Tokyo, Kyoto, Seoul and Shanghai are where foreign investigators are most likely to find themselves. But it’s out in the countryside that the natural and supernatural worlds collide with the most ferocity. Maybe it should just be a collection of scenarios.

I’m also hoping that other people will want to expand on the setting as well. One of the things I really love about the Cthulhu Mythos and Chaosium’s Miskatonic Repository is that authors are encouraged to add to the canon. For those curious, the guidelines about creating material for the Miskatonic Repository can be found here.

And if any aspiring scenario writers out there want to use any elements from Japan – Empire of Shadows to create their own unique work for inclusion on the Miskatonic Repository so that it dovetails into the setting, please feel empowered to do so. If you have any questions, please feel free to reach out to me at empireofshadowsrpg@gmail.com. As you can tell 10,000 words into this interview, I enjoy writing, and will be happy to reply.

14. That’s an amazing open invitation. I hope people take you up on that. I have one small criticism of the book, if you’ll permit me. Near the end of the tome, you briefly describe 29 different “Japanese Creatures” and 21 “Chinese Creatures,” but then proceed to provide CoC stat blocks for only 6 “yokai.” What kept you from providing stats for more or all of the creatures/yokai?

I certainly would have liked to keep expanding the bestiary, but at a certain point, I had to keep in mind that I was fast approaching 400 pages. Also, I don’t think the book lacks for statted monsters. If you look on page 397, there’s an index of the monsters in the book. I think of the 34 creatures noted, almost all have stat blocks (or if not, references to their stat blocks in Chaosium books like the Malleus Monstrorum or 7th Edition Rule Book). The six in the back just happen to be the ones most referenced, so instead of repeatedly entering their stats every time they appeared, I opted to put them in the back, with a little note wherever they appeared in the text to refer to the Yokai Bestiary section.

I do think this brings up an interesting difference between creating material for D&D versus CoC. If this was a D&D module, I absolutely would have statted out all the possible creatures that could be encountered, and this would have been done in conjunction with scaling those monsters for a particular range of PC experience levels. In D&D, the expectation is often that combat (physical or magical) can overcome adversaries with the goal of rising in level to allow the characters to face even greater opponents in the future. In CoC, pretty much any Mythos creature encountered can cause heavy sanity or hit point loss and the odds are most characters aren’t going to survive head-to-head encounters with their lives or sanity. Often, the best option in CoC is to avoid fighting the monsters (which are often unnerving presences on the periphery) until the investigators have researched them and discovered the McGuffin required to dispatch them. The fun of CoC is the knowledge that behind any door could lurk a nameless horror that you are powerless to stop, and the only hope you have is to stay one step ahead of those dreadful sloshing footsteps until you acquire the forbidden (often mind-shattering) spell or artifact required to send it back into the chaos from which it slithered.

What this also means though, is that the stats of the creatures in CoC are often less important than providing the story-driven means of defeating them that the characters learn through sleuthing. I mean, I love a good shotgun, but it’s not going to do much to Cthulhu, whereas all those puzzle pieces and hints you picked up on the way to R’lyeh can really pay off, assuming your sanity holds out.

I do agree, I’d love to see stats for all those beasts. Maybe there’s someone else out there ready to tackle the Big Book of Yokai Monsters?

15. That is honestly a very tempting project. Okay, so you list dozens of books, several TTRPGs, about 20 songs and 16 movies and TV shows as inspirational media. If you had to narrow it down, what would be the top 3 movies or TV shows that you would recommend for Keepers who wanted to inject the best sensory impression of the setting on their players prior to their first session?

1. Teito Monogatari (aka Doomed Megalopolis). If you want to see one of the most gonzo, out there, ambitious but bizarre Japanese films of the 1980s, look no further than Teito Monogatari (you can find it on YouTube). It’s set in 1920s Tokyo and has magic, evil spirits, geomancers, earthquakes, a plot that makes no sense, but is so full of weird 1980s eye-candy that you can’t help but love it. It’s actually sort of like watching a Call of Cthulhu game where the Keeper basically gives up and starts throwing everything and the kitchen sink at the players to see what’s going to happen, then summons an elder god to wipe Tokyo off the face of the planet, because, hey, that’s what you have to do sometimes.

2. Gyeongseong Creature. If you have Netflix, this one is definitely worth watching. It’s set in Korea in the early 1940s during the Japanese occupation and feels like a Call of Cthulhu session. Evil scientists have taken over a hospital and are turning hapless victims into murderous monsters. An eclectic team of investigators (each with his or her own agenda and backstory) comes together and must enter the hospital, rescue the victims, stop the bad guys and face the ultimate Mythos-type monster unleashed in the dungeon like maze underneath the hospital, all while learning sanity shattering truths.

3. A Page of Madness. This is a silent film from 1926, but don’t let that fool you. It’s an avante garde masterpiece of madness set in an insane asylum in 1920s Japan. A former sea captain becomes a night watchman at an insane asylum where his wife is being kept. The cause of the wife’s madness is revealed in parallel with the watchman’s own descent into insanity, as he tries to protect his daughter’s future from the sins of the past. You can watch it on YouTube.

Audio honorable mention:

The National Diet Library of Japan has an amazing audio collection to set the tone for your sessions. Download a few inspirational tracks like The Enchantment of Summer sung by the lovely Chiyako Sato.

Race and Authority

16. I can’t wait to watch all of these. Okay, here’s a bit of a touchy subject. I was once kicked off of a game jam on Itch.io for not being the right ethnicity for the subject matter that I was writing about. What would be your defense against criticism of not being Japanese and yet writing all about the history and culture of Japan for people to use in an RPG?

It’s too easy to live in fear about what other people think. If you want to see something happen, make it happen. If you want to write a book on a subject you’re passionate about, write it. If someone is too bigoted or narrow minded to read it, don’t waste your limited time on this planet trying to change their mind. Write it for you. Write if for curious and open-minded people. Write it because it is a subject worthy of being documented.

I spent two years writing and researching Japan – Empire of Shadows. It has received praise both here and in Japan and I stand behind what I have written. That’s about all I have to say on the subject, and you know me… if I had more to say I would.

Okay, I do have one more thing to add. It’s a Zen koan that seemed appropriate.

“Nan-in, a Japanese master during the Meiji era, received a university professor who came to inquire about Zen.

Nan-in served tea. He poured his visitor's cup full, and then kept on pouring.

The professor watched the overflow until he no longer could restrain himself. "It is overfull. No more will go in!"

"Like this cup," Nan-in said, "you are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?"”

That would be my answer.

17. Amen, brother. Thanks for saying that. Speaking of Japan - Empire of Shadows being received in Japan, what are the chances that the book could be localized in Japan? Have you already knocked on Kadokawa’s door with this one?

I suspect an official Japanese release is unlikely, even though I have heard many Japanese fans express a huge desire for it. There are three main reasons for this. 1) Kadokawa already has a Taisho Era sourcebook, “Cthulhu & Empire.” 2) J-EoS is not an official Chaosium product, but is part of the Miskatonic Repository and thus is more “fan fiction” than official canon. 3) The book uses Imperial family members as NPCs, talks about Japanese atrocities and Japanese publishers traditionally like to play it safe when it comes to such controversial topics.

I know there is a fan-translation in the works and I’m touched by that. I peek in on “X” (fka “Twitter”) every so often to see how it’s going. I keep waiting for a note like, “this guy is totally wrong,” but luckily most of the feedback is like “影の帝国マジでこれ書いてるの日本人じゃないの?日本人への理解度高すぎないか???” (“Shadow Empire, Seriously, aren't the people writing this Japanese? Isn't the level of understanding of Japanese people too high???”). So that’s encouraging.

I would like to note that Chaosium has been very supportive of the book on the Miskatonic Repository and at their conventions. Michael O’Brien and Nick Brooke in particular have been wonderful, mentioning it in posts and making physical copies available for sale at Chaosium’s Community Content tables at conventions. Schlepping a stack of 400 page hardcovers around is no small task. Mike Mason gave me very kind notes and feedback on the book which I took to heart and incorporated.

18. Can you provide readers with a list of your publications, translations and where they can find you online?

For those curious about my tv and film credits, you can see them on imdb.com.

I’ve uploaded most of my TRPG translations to the Internet Archive.

You can find Japan – Empire of Shadows on DriveThruRPG

I’ve translated two scenarios by Japanese authors that are available on DriveThruRPG:

Makami Sakura (Cherry Tree of the Wolf God) and Bride of the Goat.

If anyone has any questions, I can be reached at empireofshadowsrpg@gmail.com

Before going, I wanted to share a pair of my favorite Japanese words.

災 (“wazawai”) is the kanji for “disaster.” Just look at it. That is totally a disaster. And it’s a great example of how “radicals” work in Japanese. 火 is fire (look at those flames) and 巛 is water (a wavy river). Just remember water over a burning fire and you’ve got “wazawai” (a disaster).

クトゥルフ (“kuto-u-rufu”) uses katakana to spell “Cthulhu.” And you thought “Cthulhu” was hard in English…

Thank you very much for the opportunity to talk about Japan – Empire of Shadows and about so much else. I like to think that international cooperation and understanding begins with curiosity. I hope that this interview has sparked some curiosity about Japan and Japanese TRPGs. There is a world of great gaming going on out there. Go out, find it, share it and game on!

– David Trotti

Note: You can get Trotti’s seminal Call of Cthulhu supplement set in 1920s-30s Japan, Japan: Empire of Shadows, from DrivethruRPG in PDF and print-on-dem

Dave, I wanted to compliment you on this fascinating and deep interview. Great work, as always! David Trotti is fascinating and I hope all his creative efforts bear fruit. Empire of Shadows looks tremendous.

But the interview also highlights the tragedy of RPG writing and design: there is no money in it. Absolutely no way to support a middle-class family unless you're one of the very, very few whose name attached to a project ensures success (RDL, Ken Hite, Gaska, for example). Empire of Shadows (400 pages, color, art) represents years of work by <checks DriveThru> ONE (!) person and sells for $15 bucks. And even at that price, people will quibble. It's tragic that so much brilliance gets little more than appreciation in return.

Do you think that game designers (goes for video games too) will ever get the recognition they deserve on par with authors or film directors for bringing so much goodness to human culture?